Ethical Dimensions in Research: Children as Co-Researchers

Ethical Dimensions in Research: Children as Co-Researchers

For Rachel Bray, researcher at the Oxford Institute of Social Policy at the University of Oxford (UK) and specialist in childhood, family policy and poverty, working ethically with children is about understanding their everyday lives and social worlds, and trying to “get into their skin”. Speaking about her experience with children living on the streets of Kathmandu, Nepal, and with young teenagers in South African post-apartheid society, she explains the importance of qualitative and participatory approaches that give children an active role in research based on a relationship of trust and mutual respect. Enabling children to be co-researchers means giving them a space to express themselves where their voice and thoughts are heard.

As ATD Fourth World prepares to embark on a 3 year participatory International research project in link with Oxford University; Rachel Bray is interviewed by Monica Jahangir of ATD Fourth World.

When you started your research about street children in Nepal, you were volunteering in a local non-governmental organisation (NGO) that offers drop-in facilities for children working and sleeping on the streets. Why was it important for you to be in that space, rather than working on your research more independently?

Rachel Bray: As an anthropologist I wanted to be in that space and understand how people, social organisations, society, were thinking and considering these children living on the streets. There are different ways in which society regards them: either with extended care because they are considered more vulnerable than other children, or through denigration or exclusion on the basis that they are doing something that children should not be doing. Also, another reason for my presence was that I wanted to befriend the children, gain their trust, and start to see the world from their perspectives I wanted to understand whether they really were technically homeless and as vulnerable as NGOs or international organisations tended to depict them, or if they developed social competences allowing them to adapt to their changing environment.

So for me these two poles – the political portrayal of children as victims or delinquents on one side, and the political implications of the experience of young people on the other – were not two poles really; they were two sides of a coin. Being in this setting enabled me to understand that these children were capable and vulnerable at the same time. They relied on NGOs to fulfil some (but not all) of their needs, while at the same time NGOs were somewhat dependent on having a needs group of “street children” to justify their existence and to raise funds.

How did you come to adopt a qualitative approach for this research project? Why did you choose to work not about the children but with them?

Alongside my voluntary role in the Nepali NGO, I was working with a biological anthropologist collecting a series of data on height, weight, fitness and stress levels. These told us a lot about their physical health and provided some clues about their psychological well-being. In a survey, we also asked young boys aged 9-17 years where they came from, what they did before coming on the streets and why they came on the streets. I quickly realised that this method was giving us a distorted picture of reality. I could tell in our discussions with the boys that they had little or no motivation to tell us anything in depth about their lives and the reasons which prompted their choice to live on the streets. They didn’t know us very well; the questions we were asking were surface level and not appropriate. They induced the idea that the choice to leave the family home resulted from a single decision circumscribed in time. Whereas it soon became clear that it was a series of events, opportunities, and coincidences that led them to sleeping rough, begging or rag picking. I realised the survey approach was not getting us anywhere; and so an ethnographic approach combining sharing meals and work time, conversation and building friendships was the right way to go.

Talking about befriending, how did you manage to foster these relationships of trust and friendship so children could open up to you? In which spaces?

What was interesting was that the children saw me as a friend of the NGO – that is to say as someone close to the NGO, close to the staff but not totally part of the staff. This somewhat hybrid role allowed children to have trust in me as an individual, and a friend of the NGO. And I also spent a lot of time with children outside, which other social workers would not necessarily do. I would be going to the junkyard with them, early morning, around 5:30 or 6 am, taking tea with them, listening to stories of their nights’ work scrap collecting, going to eat with them on certain occasions, going out in the mountains on day trips sometimes, all sorts of things. And they started to talk to me about their ambitions, such as wanting to become motorcycle mechanics. They identified successful companies in the city and asked me to accompany them in approaching directors to discuss training opportunities. Together we organised six-month apprenticeships for five young men in their late teens.

I believe that one way to build trust with children is to show my trust in them, through concrete actions. I would for example lend my bike (something no one else dared to do!) or pay for tea, knowing they would return the favor in the coming days, something they found to be mutually honouring This is what anthropologists sometimes call informal delayed reciprocity. At the end of the day, it really boils down to the best way possible of “walking the walk” with these children, and being in spaces where I understood both their everyday concerns, desires, opportunities, connectedness…, as well as the challenges and barriers produced by the society around them.

In 2001, when you joined the Centre for Social Science Research at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, you further explored participatory research, this time involving teenagers directly in the process as co-researchers.

In this research project, we wanted to understand how the end of apartheid affected the life experiences of South African children and youth. What was everyday life like for the first generation of young people growing up in a democratic South Africa? What were the similarities and differences in the lives of teenagers coming from neighbourhoods that were once separated based on race and class?

During field visits to schools in the Fish Hoek Valley (south of Cape Town), we explained to students that we wanted to understand young people’s lives from their own experiences and questions, for example through weekly meetings in focus groups and art activities, and discussion with other young people about social, political, historical and personal issues. Soon, youngsters aged 17 or 18 expressed interest in joining our research project. They were eager to gain skills in social research (such as how to conduct an interview, use recording tools, and also to have the opportunity to write, work with journalists, etc), but also to meet other young people from different neighbourhoods and find out about “what was going on in the lives and minds of young people living in the valley”, as said one of the teenagers. These six young researchers (three boys, three girls) called themselves the “Tri” group to refer to their interaction as they came from three sociologically, culturally and historically different

What were you careful about in your work with these young researchers? What were the methods used to engage them?

We aimed to go beyond the tokenistic or even exploitative involvement of young people found in many studies. Our research was designed to provide young people with a space where they could raise and pursue topics they felt were important to them.

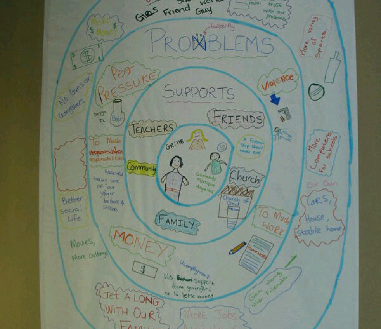

For this, we used a variety of methods, some open-ended, others specifically designed to obtain additional information to some quantitative elements we already had. We kept journals of our observations and conversations with and about children and adolescents. We combined one-on-one interviews with participatory group activities, including art and drama, which enabled young people to express themselves. For example, we asked young people to map their neighbourhood, which allowed us to understand their mental representations of where they lived, to map their support networks (family, circle of friends etc.), or to illustrate their life stories with themselves as the heroes. Other young people, who were struggling to express themselves, were equipped with cameras, so they could to take photographs illustrating their diaries.

After an introduction to interview techniques and issues of consent and confidentiality, young researchers from Tri group also interviewed their friends and relatives, about their everyday lives or on personal aspects. We always cross-checked data produced by young researchers just as we did for our own data. Our weekly meetings with the group allowed them to share their impressions and questions on ethical issues3. We associated them in the analysis of the collected information. Not only did we learn a lot from their research, but the partnership with Tri became an important source of learning about how to manage and conduct youth-led elements of a wider research project.

In your discussions with young people, you must have discovered some very personal aspects of their lives, especially for the most vulnerable ones facing poverty and violence. How can these children experiencing very difficult lives be protected to avoid further harm?

It could happen that some children involved in our research were in situations of great vulnerability or violence. If a child is beaten or abused, then one must stop and think as sensibly as possible with the child, trying to find out how much the child is willing to disclose, because there might be many reasons why the child doesn’t want to disclose very much. And we must understand what professional support exists in the immediate locality in order to know whether it’s better for the child to alert a medical or social service really close to their home, or whether this could lead to social exclusion owing to close connections between staff and family or neighbours, which may compromise the child’s privacy and make them vulnerable to further risk. It is also important to remember that in South Africa, segregation has resulted in high disparities between neighbourhoods in terms of health and social services.

To sum up, an ethical response to face violence and vulnerability must always be based on a deep understanding of the child’s family relationships and neighbourhood relations, in order to establish a more protective solution. Of course, this has to go through a good talk with the child about who she considers to be the greatest source of protection in her life.

What was the impact of this participatory research project on the teenagers? Did it contribute to their emancipation?

The research project allowed them to initiate a reflection about their lives, identities, neighbourhoods, teachers, and relationships with social services. [They could even] deconstruct the stereotypes they [might have had] about those who lived in different neighbourhoods. When the Tri group shared about their life experiences, they were surprised to see that their lives could sometimes be so similar, despite all the differences between them. This helped strengthen their sense of citizenship and belonging to the “rainbow nation”.

But participatory research also had more concrete consequences in their life choices, in terms of decision-making about their training, further education, or going towards a particular career. We had outstanding examples of two young people taking full advantage of the space they were given to express themselves during the research. Ganesh, a street child I met during my doctoral thesis, had an undeniable artistic talent that I had encouraged him to develop. He is now successfully based in Amsterdam, after having studied at the Rietveld Academy, a renowned art school in the Netherlands. The other is a young South African participant, Simphiwe Ndzube, who had enjoyed our art-based methods and decided to continue on this path. He is now a well-recognised artist in his country. So the space for expression and creativity offered through participatory research can be a rare occasion for young people to help reveal themselves and reach their full potential in their lives and careers.

Map of ‘our community’ by 9 to 13 year old township residents.