Bristol Poverty Institute Webinar

On 11 June 2020, the Bristol Poverty Institute hosted a webinar on “Poverty Dimensions of COVID-19 in the UK”. ATD Fourth World was represented by Thomas Croft whose remarks are below. A video recording of the webinar can be seen here.

Thank you for this chance to contribute to the discussion about the effect of the COVID-19 crisis on people living in poverty in the UK.

ATD stands for All Together in Dignity. In the UK we are a small charity supporting families in persistent poverty, mainly in London and the South East. We are a member of the International Movement ATD Fourth World, an NGO with consultative status at the UN’s Economic and Social Council and working in thirty-three countries around the world.

Our approach to overcoming poverty is human-centred and highly participatory. We want to be led by lived experience of poverty, which means that working in partnership with people directly experiencing poverty is at the heart of our action and our governance.

It is terribly important at moments like this, when society is under stress and the status quo is being widely questioned, that the voice and thinking of our most vulnerable citizens is included in the debate.

I’d like to talk to you about the importance of participatory research in understanding the multi-dimensional nature of poverty, tell you about some of our findings in this area and then share some of things that people are telling us about digital exclusion and life in lock-down.

The messy reality of building knowledge collaboratively

This slide is a bit blurry. I found it when I googled “collective knowledge” but maybe its blurriness is apt as it depicts the messy reality of building knowledge collaboratively, particularly of social issues like poverty.

I don’t need to tell you that poverty is complex. Poverty effects all aspects of a person’s life. Because of this, if we want to understand poverty in all its forms we need to listen to people’s lived experience and we need to value the knowledge they carry.

This why participatory research is so important. When it is done well it is a means addressing epistemic injustice – or removing the philosophical jargon – of addressing the inequality and unfairness in the way we produce knowledge.

This unfairness exists when the experience and knowledge of someone or some group is ignored or denied or exploited. But it also occurs when people are denied the opportunity and resources to make sense of their experience themselves: to name it and conceptualise it in order to contribute to the societal effort to build knowledge on a more equal footing.

Research into multidimensional poverty

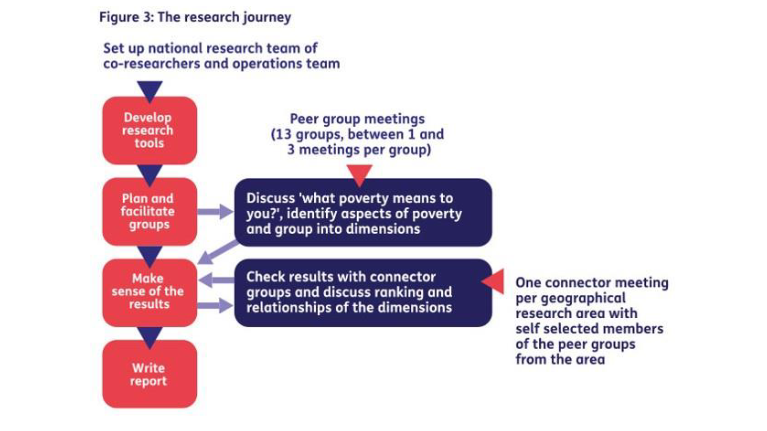

Over the last three years, ATD Fourth World together with academics from Oxford University organised research into multi-dimensional poverty in six countries: Bangladesh, Bolivia, France, Tanzania, the UK and the USA.

It was very ambitious in participatory terms. In all countries research teams were recruited which included professional researchers, but also co-researchers with direct experience of poverty, either through lived experience or through their professional life – sometimes both. In the UK we assembled co-researchers with backgrounds in peer support, community activism, journalism, health, policy, and academia.

The co-researchers guided the research journey from its design, through data collection in the field, to analysis of the results and the co-authoring of the final findings and messages.

In the UK, the study was called “understanding poverty in all its forms”. We organised peer groups in London and the South East, the North of England and the central belt of Scotland. The groups brought together between six and ten peers who met together several times sharing what poverty meant to them and then discussing and agreeing a set of poverty dimensions.

Each group was formed around either lived experience or professional experience of poverty. Some members from each of these peer groups were subsequently involved in fine tuning the overall findings.

Each group was formed around either lived experience or professional experience of poverty. Some members from each of these peer groups were subsequently involved in fine tuning the overall findings.

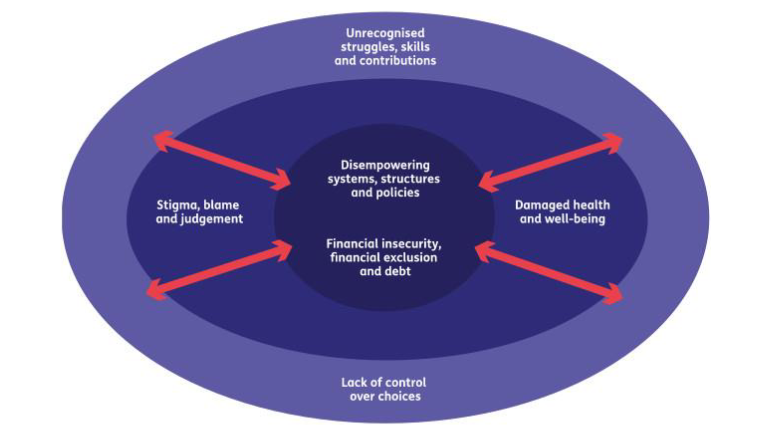

So what UK dimensions of poverty did we identify? Six in total.

DISEMPOWERING SYSTEMS, STRUCTURES AND POLICIES

Economic, political and social structures can cause poverty. Policy is operated in a way that disempowers. Systems designed to support people are not working in ways that people want. Systemic cuts in funds for needed services have exacerbated inequality.

FINANCIAL INSECURITY, FINANCIAL EXCLUSION AND DEBT

Financial insecurity means not being able to satisfy your basic needs. Worrying about money every day causes huge stress and misery.

DAMAGED HEALTH AND WELL-BEING

Poverty is bad for health and can shorten life. It has a negative impact on physical, emotional, mental and social well-being.

STIGMA, BLAME AND JUDGEMENT

Misrepresentation about poverty in the UK and a lack of understanding lead to negative judgement, stigma and blame, which are deeply destructive to individuals and families. Prejudice and discrimination result in people in poverty feeling they are treated like lesser human beings.

LACK OF CONTROL OVER CHOICES

Poverty means a lack of control over choices and opportunities. Over time this can lead to increased social isolation and risk, as well as restricting people’s social, educational and cultural potential. The lack of good options reduces people’s control over their lives and traps people in repetitive cycles of hardship, disappointment and powerlessness. Lack of opportunity and choice increases risk and restricts options. Poverty is dehumanising.

UNRECOGNISED STRUGGLES, SKILLS AND CONTRIBUTIONS

The wealth of experience and life skills people in poverty possess is not recognised enough. Too often, public discourse undervalues the contribution that people in poverty make to society and to their communities while facing the daily impact of poverty.

In the field we asked people how the dimensions of poverty they had identified connected and related to one another. The overall view was that the dimensions of financial insecurity and disempowering structures where the initial drivers of poverty and their effects rippled outwards into the other dimensions before returning as the different dimensions compounded and reinforced each other.

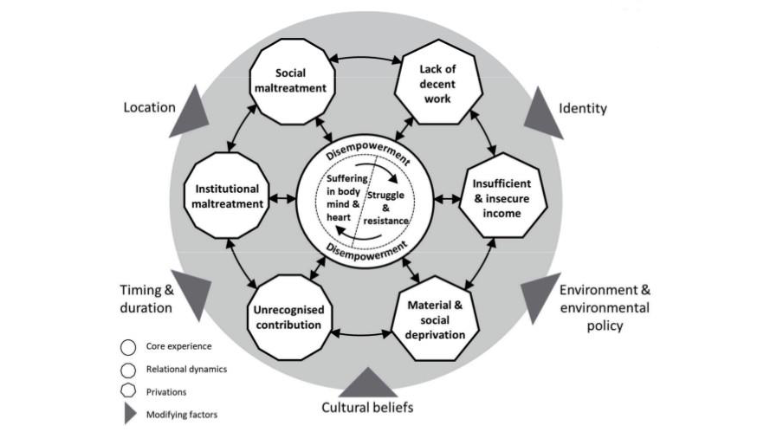

At an international level, co-researchers from each of the national teams compared and contrasted each country’s dimensions and then proposed an integrated model which you can see here. It is discussed in detail in the international report “the hidden dimensions of poverty”.

Very quickly, it shows nine dimensions:

-

Three covering the main privations of poverty

-

Three describing relationships between people in poverty and the rest of society

-

And three capturing the core existential experience of poverty

It also shows five modifying factors that influence these dimensions in different contexts

One of the things our research really highlights is the emphasis and central importance that people with direct experience of poverty place on the psychological and social impact of poverty.

With this in mind, I would like to share a few things we are learning about how the COVID-19 crisis is affecting people, in particular how the lock-down and other measures have revealed and exacerbated the digital divide. Over the past months we have been talking to people through our lived experience networks in Scotland and England about this issue.

Internet is not a luxury

Under lockdown, most people are using the internet more than ever before. For those who cannot afford the devices and wifi that could connect them, the digital divide feels wider than ever. The BBC notes that only 47 per cent of people on a low income have broadband internet at home.

Even before the lockdown, when libraries were open, short limits on computer time were problematic. One woman we know would stand outside the library to use the wifi while applying for jobs on her phone. “Having only an hour or less to use a public computer creates enormous pressure when you have to prove that you’ve applied for enough jobs to avoid being sanctioned.”

In addition to needing smartphones and wifi for further education, work, and administrative requirements, as Gloria from Glasgow explains:

“It’s really significant to have internet access because everything these days is done electronically. Not having wifi is like being locked out of the world. I used to use wifi on the bus to see the news. At the beginning of the lockdown, I felt locked out because I didn’t know what was going on. And if you have the internet, you can phone people for free with WhatsApp even if your phone is not topped up — but if they don’t have internet, you’re stuck. The internet is not a luxury at all.”

Swallowing pride

In rural Lancashire, 17-year-old Tia also found the limits much too short for homework assignments that require extensive research. Even worse, she says her local library chose to close entirely during after-school hours.

People in poverty have always had an uphill battle to access the internet. Now that social distancing measures have pulled the shutters down on public places that offered free access, that struggle is even harder.

“Before the lockdown, my daughter stayed after school every day to use the internet there for her homework. Now, without wifi of our own, I had to swallow my pride to ask our neighbour if we could piggyback onto his network from our flat. He agreed, but I feel like I should be able to chip in for his bill so that I don’t have to rely too much on him.”

Although some schools have loaned tablets to students who need them, one woman’s daughter, age 15, received nothing. Before making this arrangement with her neighbour, Gloria said: “I had to buy a pay-as-you-go bundle on my phone because otherwise she could not do her homework.”

Pleading for wifi and having to rely on others

In addition to supporting her daughter’s schoolwork, Gloria is studying for a health-care qualification, learning to give injections and calculate medication dosages. She used to go to the library to do her coursework.

“Even then it was difficult because of the limits on your time. You can’t stay very long if you need to go home to look after your child. For assessments, we need to print things, so I would pay 10p for each page. Now that I’m using my neighbour’s wifi, I took two assessments online at home — but I was really scared of getting cut off in the middle. I had to plead with him not to use the wifi for anything that would interrupt my network during the exams.”

Barriers to accessing benefits

The benefits system has been moving steadily on-line. People struggling with access and technology can receive sanctions for a perceived failure to comply. In Feltham, a woman describes the challenges she faces in looking for work and demonstrating that she remains qualified to receive the Job Seekers Allowance, even in the midst of a national lockdown:

“There is no rest or break for me at the moment. I don’t have the luxury of stopping looking for a job. So I don’t get sanctioned and still get to receive my JSA benefit I have to stay in contact with my job agency. They have asked me to download an app to do a video chat for some sort of training next week. So I have to make sure my internet allowance is topped up.”

Patricia, who lives in London, has a job on a zero-hours contract and needs internet access to communicate with her employer:

“They email me my hours. If I didn’t have wifi access, they’d have to text or phone me, which I know they can’t always do. And since I haven’t got access to a computer, I can’t print off my time sheets. I have to ask someone on the staff at work to do it for me. But I don’t like having to rely on anyone else to print off stuff for me.”

We know families where a new baby was born during the lockdown; but lack of access to the internet prevented the parents from completing forms necessary for child benefit payments to begin.

Standards in the justice and care systems compromised by moving on-line

Many family court proceedings are now held remotely via telephone or Skype. ATD Fourth World asks how fair and empathetic such hearings can be. Some judges are also raising this question, for example here, writing for the Transparency Project.

The closure of child contact centres during the pandemic prevents contact between children in foster care and their birth families.

The lockdown is reported to be causing a sharp increase in family court care proceedings. Research shows that families in poverty are the most likely to have their children removed into care. Some local authorities take far more children into care than others.