The impact of poverty in social care

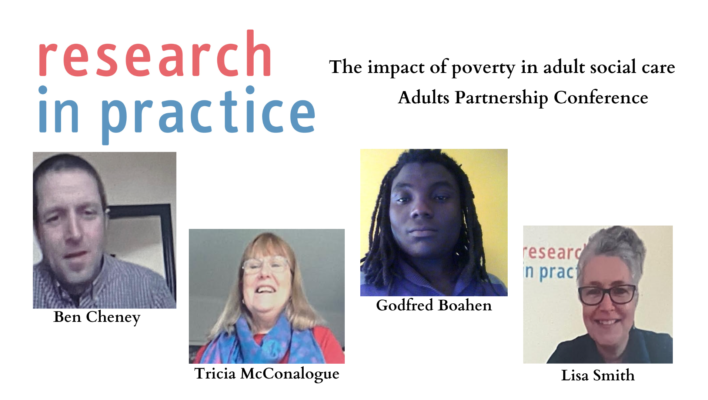

On the 9th of February, Research in Practice hosted their yearly Adults Partnership Conference titled ‘The impact of poverty in social care’. ATD Fourth World was invited to facilitate a key presentation, which was led by Tricia McConalogue and Ben Cheney. Lisa Smith, assistant director of Research in Practice, facilitated the conference alongside her colleagues.

The purpose of the event was to explore how adult social care can operate with the aim of understanding and exploring different aspects of poverty. As Professor Kate Morris has written, poverty is the ‘wallpaper of practice’ in social work being ‘too big to tackle, too familiar to notice’. The structural root causes of poverty are staggering and overpowering. Professionals at times find it more straightforward to avoid the problem and focus instead on ‘reshaping’ individuals without further understanding. However, professionals in the social care sector have proved that using an anti-poverty framework, working with those within the community who have lived experience of poverty, can reap advantageous outcomes for all.

In addition to ATD, speakers at the event featured members of Hackney and Newcastle City Councils, and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Dr. Godfred Boahen, Principal Social Worker at Hackney Council, opened the floor for discussion about looking beyond the objective measures of poverty and utilising a strengths-based approach.

Drawing on strengths

Boahen said: “Poverty can hinder people from actively participating in decisions about their own care and support needs, and that therefore draws our attention to practise in a strengths-based way. […] We’re always seeking to draw on people’s strength, their own internal resources, to be able to overcome the situation; while at the same time connecting them to those rich and powerful networks within their communities, which are so important to a holistic sense of self. And all this then has to be underpinned by a rights-based framework by saying:

we’re talking here about people’s human rights, what we, as a society, think what a basic standard of decent living looks like. This calls for a new partnership between local authorities, the government, and third sector organisations.”

Boahen suggested that a powerful framework to draw upon with regards to this is the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Experts on their own communities

Jenny Zienau, Strategic Lead at Hackney Council further contributed key information. When speaking of the wide-spanning obstacles Hackney faced during the pandemic, she highlighted that: Without our community partners on the ground there’s absolutely no way we could have really met the scale of the challenges”. Giving those living in Hackney a voice was significant, as they are the experts of their own communities. Zienau stated “It’s not just what we do, it is how we do it. It’s the humanity and the compassion that Godfred described”.

They found balance between immediate financial support for material impacts of poverty and also prevention, which is crucial for the borough. She highlighted that it is not simply a matter of “only looking at how to prevent adversity, and the kinds of things that make life chances much more difficult for our communities, but also the ways that we can build resilience, both in individuals and in communities.

Open conversations

Charles Clark, System Convener at Hackney Council, explained how they have launched a grants programme where 20 community-based organisations have received capital. He explained a method of visiting voluntary sector organisations to have open conversations without an agenda in place. Clark explains that they do this so they can “ask questions about who they’re worried about, what are the barriers for them working well with the council”. They will then write those up and think deeply about the strong concerns within the council’s conversations. A great example of an organisation mentioned was the Hackney Play Bus, where children can play and parents are given information about community happenings.

Godfred concluded that when he spoke to local volunteers it increased their self worth having an involvement; forming friendships, learning skills, and importantly contributing to community. He said: “When I reflect on all this as a social worker, sometimes I think: these are areas, these are residents, these are citizens that I may not have been able to reach if I had my social work hat on, with my folder, saying ‘I’m going to do an assessment’.

It’s a completely different kind of language that grassroots organisations working in anti-poverty speak, from sometimes what we would say when we’re thinking too much about poverty through that sort of objective, income lens, or that risk and safeguarding lens.”

Reflections from ATD Fourth World

Ben Cheney & Tricia McConalogue have both been involved with ATD Fourth World for many years. Ben was part of the National Coordination of ATD UK in 2014-19, and Tricia represented ATD at the United Nations in 1994. They began by sharing ATD’s research ‘Understanding Poverty in All Its Forms’ placing emphasis on its participatory methodology, through which six activists with lived experience of poverty formed a team of co-researchers, in collaboration with academics at Oxford University.

They each read quotes from the research, “Poverty means being part of a system that leaves you waiting indefinitely in a state of fear and uncertainty. […] In poverty, we might sometimes feel broken by experience, but we are generous in spirit, solidarity and community spirit” to name just a few of the ones voiced.

‘Leading the team made a huge difference to her’

McConalogue demonstrated to the audience her work at Bridging the Gap, a great example of what it means to recognise people’s struggles, skills and contributions. In the Gorbels, Glasgow, this organisation brought together people from all walks of life including asylum seekers, refugees, and also people with deep roots in Scotland. The peer support was profound. Food was a central part of this project, with members of the community volunteering to cook for the whole group of 60 to 100 people. At times people did not realise their capacity to contribute their skills; but through warmth, food and activities.

McConalogue described how she supported cautious individuals to draw out their resilience and expertise:

One particular girl had learning difficulties, and she wanted to volunteer. It didn’t matter if you could only make tea or whatever. So she said she would cook macaroni and cheese. We were all thinking ‘how is she gonna do it?’ but the people just came together. She just told them some of the ingredients, and then people were saying ‘do you think you should add this?, do you think you should add that?’ And at the end of the day, the macaroni and cheese was great because it was done as a team. But she still felt she’d done it because she felt she was leading the team. That made a huge difference to her.

Overcoming discrimination

Of course challenges arose within this process. The community was diverse and discrimination sometimes came into play. This was sometimes a case of learning particular patterns from older generations, or a matter of being surrounded by growing frictions within the community. McConalogue explained, “It can even be the fact that, when asylum seekers moved into the Gorbels, people felt, ‘you know, they’re getting everything, they get this money we don’t get’.”

As a response the team would intervene, teaching in integrative ways. McConalogue said: “There was one particular woman who refused to make eye contact with people of different nationalities and she steered away from them, so we took her on a storytelling weekend.

Taking people away from the stresses and strains of everyday life and enabling people to interact through stories was a tool we used to break down barriers. We used to do ‘favourite day, favourite song’, and that opened people up.”

They would come with a song that would remember the mood of their favourite day. Asylum seekers would talk about their favourite day and also about the struggles in their country, it just completely broke down barriers. Soon everyone would be exchanging music and then phone numbers to get to know each other.

Reshaping the model

Cheney added valuable knowledge about strengths-based practice. As a social worker himself, he recognises that it is powerful to pull out people’s strengths and their ability to play a part in community; however, it can be a double-edged sword. He explained that “It tends to get used in adult social services as a way of not spending any money because we tend to go in and say: “You’ve got this wonderful family about you or wonderful community around you. So you can meet your needs and we don’t have to do anything.”

It is important to have that balance, to recognise strengths but to also reshape the model of the system and increase awareness of what can be made available to the people.

Cheney conveyed another example where community initiatives could be better utilised: “I went to a food bank recently and it was very dehumanising. It’s run by very nice people, all very well intentioned. But the poor guy we took there had to be interviewed. He had to be asked a question right when he came in the door. And then he had to have a number, literally a number like he used to have in the Job Center. There were reasons for asking the questions. But you had to do it all in public. And then halfway through, one of his one of his mates came in. He was embarrassed because he didn’t want to be seen in the food bank.”

Developing partnership

When comparing this to McConalogue’s community meals, it demonstrated that when conducted in the right way success can be achieved. It is about creating worthwhile co-operation. Cheney made clear that:

“Strengths-based practice means more than just recognising what people are already doing. It also means developing a meaningful partnership.”

To illustrate this to a greater extent, he shared a video which displays the positive outcomes of having these communal bonds through the project The Roles We Play.

Following their presentation and some work in small groups, they responded to a Q+A. McConalogue was asked what the audience should take away from the conference? Her response was “If people should take one thing from today, it would be to include people from the beginning to the end, as these people in poverty have skills and solutions.”