The Power of Creativity — “Memories I Can No Longer Silence”

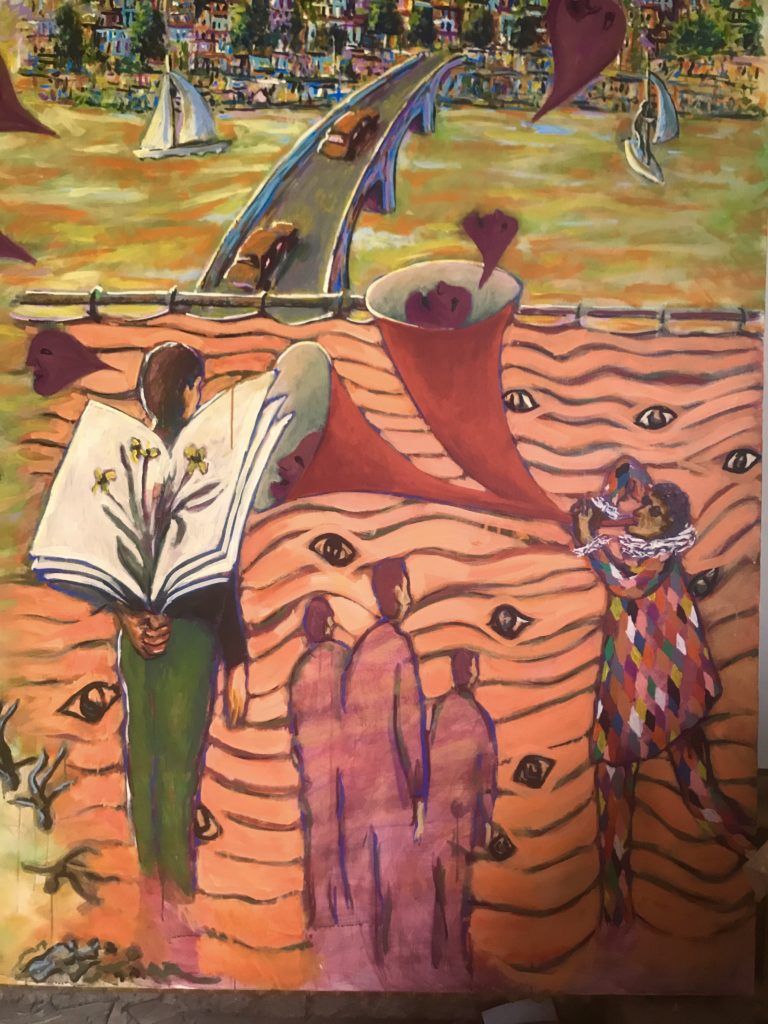

– “Childhood”, a mural by Guendouz Bensidhoum

Guendouz Bensidhoum grew up in poverty on a transit estate in France, designed as temporary housing. On 17 October 2023, as part of The Power of Creativity exhibition, Guendouz engaged in a dialogue with activists from ATD UK about “Memories I Can No Longer Silence”, his series of murals portraying different aspects of childhood, adolescence, and adulthood on that estate. Thanks to Elsa Haughton offering her talent as an interpreter, Guendouz had a conversation with Tammy Mayes, Summer Mayes and Ruth Knibbs. Here are excerpts from their dialogue.

Summer: Over in the exhibition, you can see photographs from The Roles We Play: Recognising the Contribution of People in Poverty. All the activists shown in the book are the ones who made all the choices about the photos and the messages.

Tammy: We spent ten years working on the exhibition. We learnt a lot about ourselves, but also stuff we didn’t know, like the fact that there are so many in the UK who don’t have voices and that we need a platform for us to have our say. Between 2009 and 2019, we made The Roles We Play, along with many other activists, some of whom are also here today, like Seamus, Georgina, Alison, Angela, Patricia and Amanda. Unfortunately there are also many amazing people who were involved but are no longer with us. They are missed but not forgotten, so let’s take a minute to remember Mo, Rita, Derek and Diane, gone but never forgotten.

Ruth: Over there, you can also see some paintings that were copied from The Roles We Play. Guendouz is the one who painted them. But today I want to ask him to tell us about a different set of murals he painted.

Demolition

Guendouz: This is the estate where I grew up, in Creteil, 13 km outside of Paris. I lived on this estate until I was 24 years old and my mother and sister didn’t leave until 18 years later. In 2018, we knew the estate was about to be demolished. I rushed over with two of the men I grew up with. Djamel said, “Look! It’s the end!” The emotions were palpable. It’s frightening to see a huge crane chomping away at our homes.

In the centre, where the playground used to be, we saw impressive heaps of rubble, wood, metal, and plumbing.

Thierry and Djamel’s faces were overcome with sadness, anxiety about tomorrow, the loss of their bearings, the end of this estate. For me, it’s a day that shouldn’t be forgotten.

I was gripped with the desire to paint my neighbourhood. Perhaps other people could learn from these unexpected stories.

Childhood

This image honours the girls and women of any background, who help raise younger children to keep their family together, child-mothers deprived of their youth. I painted the girl inside a heart because of the importance of love.

At first, I painted her with a book in her hand because culture is a way to escape poverty. Later, I painted over the book to turn it into a butterfly because this girl is dreaming as she pushes the pram. She’s able to forget that she has to care for her brothers and sisters. She can forget that she has no childhood.

Many girls don’t mind looking after the little ones; but still, it limits their horizons. They have other ambitions.

Now, the butterfly that the girl is holding has entered her. On her own dress you can see what she’s drawing from the book, and what might possibly be her future. At the top right of the mural, the woman with flowers on her dress represents the girl’s dreams for when she grows up. She dreams that even her dog will be happy.

‘Wearing stigmatisation’

Ruth: We see that you put a lot of beauty into this, but we know you also put harsh things there. Tell us what it was like when you went to school.

Guendouz: These children are marching into school dressed like prisoners. Every year, the poorest kids on the estate used to receive free clothes. But the clothes were made from material you never saw anywhere else, not in any shop.

It was like they tried to make the ugliest possible material so kids would be wearing stigmatisation.

All the others made fun of these ridiculous clothes. To compound the humiliation, there were the campaigns against lice. The kids in these awful free clothes would get covered in white powder by the school nurse. This didn’t happen to any of the other kids — only the poor ones.

This is why I painted the school building upside-down. I also showed a dunce cap. There is no place as humiliating as school.

Summer: They used to have dunce caps here too. Now we’re going to see your second mural, about adolescence. What was it like for you and your friends as teenagers on that estate?

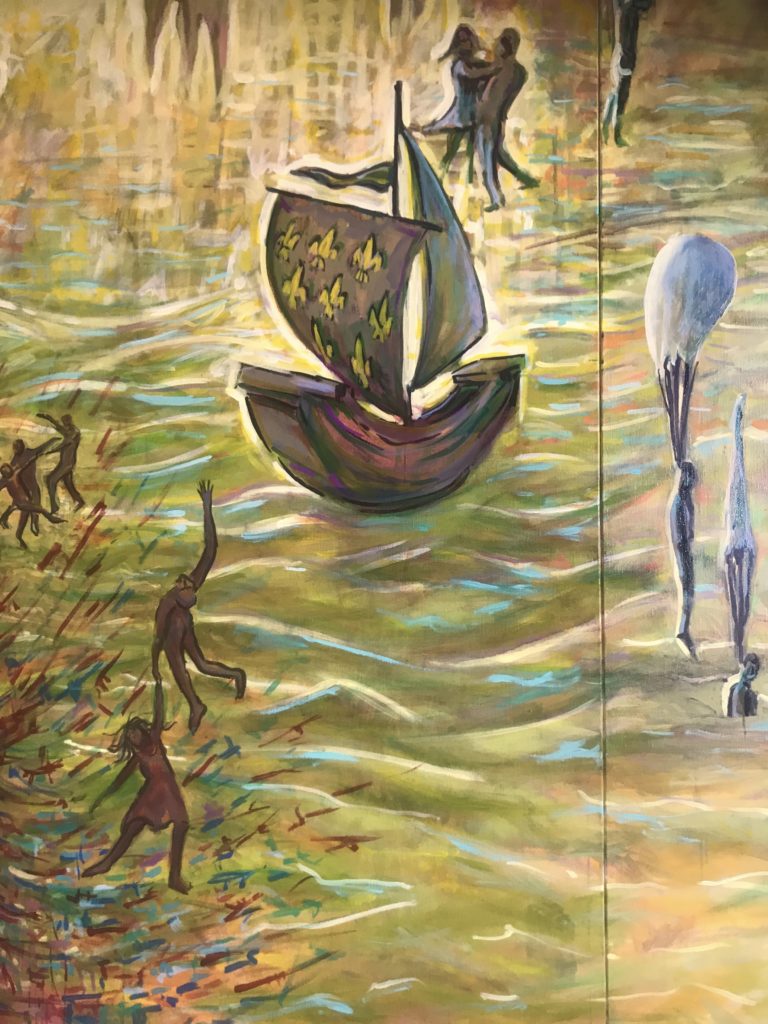

Adolescence

It was a difficult time with drug-related violence, unemployment, and a sense of uselessness. Along with all this, there was the experience of exclusion from the posh part of Paris and from the outside world. However, for me adolescence also became the time I discovered love, dreams, studies, and travel. Yet this was a fate from which most of us were barred by that exclusion from the world surrounding us.

This candle is in memory of a kid I grew up with who ran away when he was 20. We had no idea where he was until one day we heard that he set himself on fire in front of a church. So many people die young because life comes at them with violence.

The posh part of town wasn’t far away, but we knew we weren’t wanted there. It’s very subtle. It’s not fenced off, but when you have no connection to anyone, you don’t set foot there.

That’s why I painted this curtain with eyes on it. It’s only a curtain so in theory, you could push it aside — but you don’t because of the way you’d be looked at. Society doesn’t make an effort to welcome people who are different.

Summer: I’m looking at that boat. I think it’s going to pick up the young people who’ve got good qualifications to take them to the posh part of town — but it’s a very small boat, so not many young people can fit. We can see them trying to get over the river, but their parachutes are collapsing, like they’re not going to make it, as the gap between poverty and wealth is too wide.

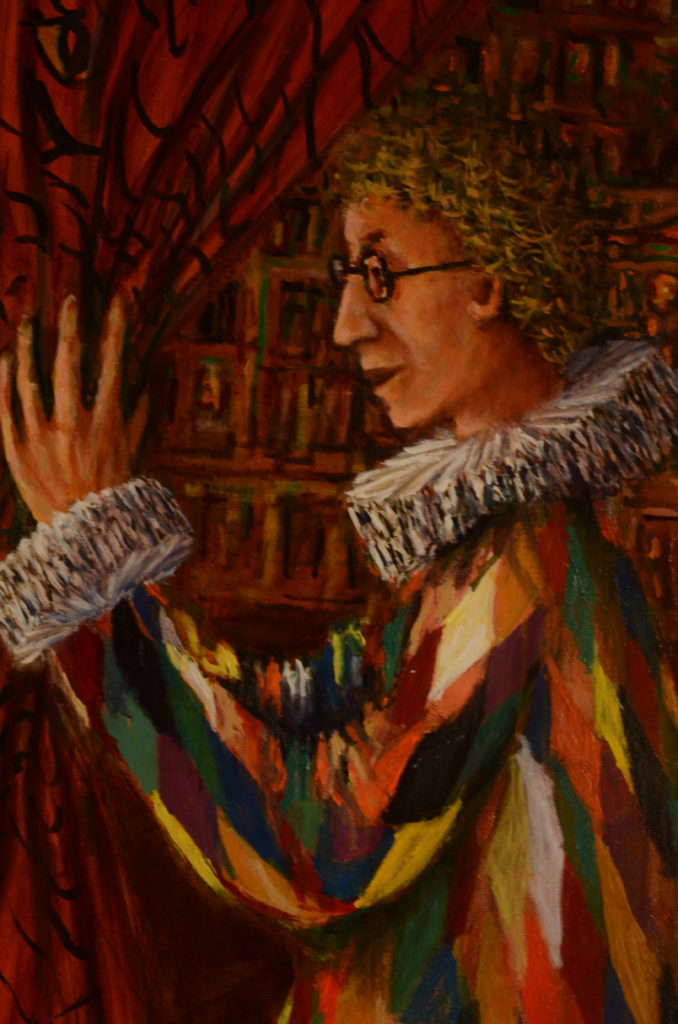

Adulthood

Tammy: We think looking at these murals helps people see things in new ways. The last mural we’re going to see is the one called “Adulthood”. Tell us about this part of the city, and how this mural connects to the other two.

Guendouz: Here, you can still see the curtain with the eyes on it, but it’s finally being pushed aside by the Harlequin. He represents another kid I grew up. He also died young, of a drug overdose, but no one ever saw him as a thug. He had a huge sense of freedom. He was a poet, always singing and he had no self-consciousness. He refused to be under the surveillance of the eyes, and so he dared to open the curtain. Only harlequins are truly free, but there’s always a harlequin somewhere.

In this mural, we see the same people as in the first murals. The girl who was pushing the pram has grown up, and she does have flowers on her dress, because she’s moved forward into real life, she’s become someone — but you also see flowers falling off her dress to the ground. Flowers are falling from her dog too because they are both disappointed that in this posh part of town, no one will welcome them.

‘They only see your past’

Up at the top of the painting, you see all the others who grew up with her and who come now to work in this part of the city, but they’re always ignored so we see they are caught up in a whirlwind.

The couple under the umbrella are the only people who live in this part of the city. They never look directly at the girl or the others. Instead, they are looking only at an image of people’s past.

When you grow up in poverty, you might change your whole life, but teachers, bosses and social workers only ever see your past.

Ruth: You spoke about the dog, but we’ve seen that throughout all three murals, you’ve put in cats as well. What’s the significance of including animals?

Guendouz: Cats represent freedom. They can go anywhere, even while people are boxed into poverty. The cat up on the lamppost looking down represents someone outside of society, watching it to try to understand why people treat each other the way they do.

The Roles We Play

Guendouz: Now it’s your turn to answer some questions. Why did you create The Roles We Play?

Summer: In 2009, we wanted to react to the really terrible things that Parliament and the press were saying about people in poverty: “scroungers, feckless, lazy”. The media would write about a man getting a huge excess of benefits, and the next article would be about someone scrounging to get by on almost nothing.

Tammy: We found It was very disrespectful, and most of it was downright lies.

There was a campaign against benefit theft called “Rat on a rat”! It felt like a war, and shame blaming on the poor. They made it out that it was our fault we lived in poverty but no one chooses poverty and poverty is not neglect.

We talked about it together at ATD, we were all getting emotional and passionate about it. We decided that we wanted to do something about it, so we started talk to each other about our lives outside of what we do together as a group. When we did, we discovered all kinds of things about each other and the ways we contribute to society so we wanted to acknowledge it.

Summer: It might be helping a neighbour, or caring for an elderly relative, or raising children.

And we decided we needed to get the general public to realise that most of us don’t fit those extremes the media talks about.

‘We shouldn’t feel ashamed’

Guendouz: What did doing this project change for you?

Summer: It gave us another avenue to put our points across. For a lot of us, this project was the first time that we had spoken out. In the process, we learned to take photos and practised speaking in public. It helped a lot of us become more confident in how we speak to people.

Tammy: Working on this project together gave us all a voice. We gained confidence to challenge ourselves more, but to also support each other. We saw that we were not alone and we should not feel ashamed to live in poverty and we weren’t to blame like the media and people think. We learnt that people in poverty are just as valuable to society as those with jobs and money, and our exhibition shows that.

Ruth: My dad isn’t here tonight, but he was also part of this project and I’m going to read something he wrote about it.

“Making this project together was interesting because you had other people to bounce ideas off of. That meant that you got a more balanced and inclusive answer about the daily lives of people in poverty. The process also meant proving to yourself that you’re worth more than other people think because a lot of people think that they’re worthless and have nothing to contribute.

Not worth less

“Each one of the people in the book do have a purpose, they do have a worth and they’re needed in society. Something as simple as standing up for the old boy next door who’s lonely and has nothing, he can’t go to the shop so you go for him. But at the same time, a lot of people who don’t get recognition come from humble beginnings. They don’t get the OBEs or MBEs. If nobody recognises it then it doesn’t exist.

“We presented this to Nottingham University, Sheffield University, and other places. The tutors were wanting us to educate their pupils about poverty because a lot of the students wouldn’t believe that there was an existence of poverty in the UK. We are experts by experience, we do live it every day. Poverty should be on the national curriculum because somebody who’s got less doesn’t deserve to be treated as less. You often find that people who have less are often treated as ‘worth’ less and they’re not.”

Guendouz: Did other people see you differently because of this project?

Tammy: I can personally say that in my experience it did change a few people’s views on what poverty was. They believed that poverty wasn’t in the UK, and people don’t see not having enough money for electric and gas and food as poverty—it’s just the norm, as it was the same when they were growing up. That’s what I find hard: that over decades later, nothing changed.

Thank you for talking to us.