Deep Structural Inequality in the Child Protection System

On 3 February 2021, Thomas Croft spoke on behalf of ATD Fourth World to the Association of Child Protection Professionals during a conference on ‘Child Poverty: Rising levels during Covid-19 and the impact on child protection. Shared best practice for 2021’. His remarks are below. Please click here to read the speech of parent activist Francesca Crozier-Roche at the same conference.

ATD Fourth World is an international anti-poverty NGO with a human rights-based approach to overcoming poverty. In the UK, where we’ve been active since the 1960s, we carry out two forms of action:

- The first revolves around supporting severely economically and socially disadvantaged families. We do this through offering advocacy and respite and by strengthening peer support networks.

- Secondly, we support individuals with lived experience of poverty to take part in projects where they can speak out and campaign on the issues that affect them.

The title of my talk is “Protecting Vulnerable Families: understanding poverty and its impact on family life”. My talk will be in two parts. The first is to present some of the findings of a recent participatory research project ATD Fourth World carried out to better understand the experience of poverty in the UK. The second is to offer some food for thought and discussion on the link between poverty, structural inequality in the child protection system, and COVID-19.

How should we understand poverty?

I want to start off by telling you about the results of Understanding Poverty in All Its Forms, a participatory study into the nature and experience of poverty we carried out in the United Kingdom. It was part of an international study which compared the experience of poverty in six countries around the world which ATD Fourth World ran with academics from Oxford University.

In the UK we brought a team of co-researchers together. Half of the team were activists with lived experience of poverty. The other half were a mix of professionals, academics and practitioners working on poverty. Together they helped us to design the project, carry out the field research, analyse the data, and write up the findings. We spoke to more than ninety people in thirteen focus groups across the UK about their experience of poverty and how they understood it. Half the participants were living in poverty and half had professional experience of poverty coming from backgrounds in social work, housing, journalism and local politics.

So, what did we learn?

We learnt the poverty is multi-dimensional. Put simply, this means that it affects every area of a person’s life. Most importantly we learnt that poverty is not only economic in nature. It is not just about a lack of money or the material deprivation that it brings.

We did indeed hear from participants about the realities of trying to make ends meet in bread-line Britain. The financial hardship, the lack of opportunities, the difficulty to provide for your family, the lack of options when you have limited and precarious resources. Unfortunately, we were expecting this.

But what we were weren’t expecting was the huge emphasis participants placed on the social and emotional aspects of poverty. How much their experience was shaped by how they were treated by others in society.

We heard about the psychological pain caused by popular narratives that judge, stigmatise and blame people in poverty.

We heard about how little control you have over your own life. How socially isolating poverty becomes. How you can feel left behind and rejected by the rest of society.

People spoke about the damage poverty does to their health and to their emotional wellbeing. We were told about how poverty is cumulative. That the longer you were in poverty the worse its effects became. Many people felt deeply traumatised by their experience.

They also spoke strongly about the lack of recognition of people’s contributions, of the roles they play in their families and in their communities. And about how many of the services that were meant to support them were either absent or were inappropriately delivered and disempowering. How frustrating and distressing this was also for many professionals working the system.

The term “child poverty” is problematic.

In reality we are talking about children growing up in families experiencing poverty; about parents and care givers living in poverty. Therefore, to get a handle on child poverty we need to consider the impact of poverty on family life.

From our research and our work supporting families on the ground, we know that living in long-term poverty cause serious material deprivation: parents can struggle to meet the basic material needs of the whole family. Children have to go without. Food insecurity and poor nutrition becomes a fact of life. Many opportunities and resources considered “normal” and taken for granted by the rest of us simply move out of reach.

This constant battle to keep your head above water, to make ends meet, to stay on top of the demands of modern life with one or both arms tied behind your back… it all takes its toll.

Near constant worry

Parents speak about physical and emotional exhaustion, about only having the strength to get through each day, about going through the motions in a haze. They tell us too about near their constant worry or anxiety. About how they will manage, but also about how they will be judged by neighbours, by their extended family, and above all by the professionals sent to assess and assist them.

It is not too difficult to see how families living long-term in poverty become socially excluded and social isolated. Discrimination on social grounds is a huge factor in this. Your children are not invited to birthday parties, your parenting is criticised, you feel ashamed, you suffer a thousand humiliations.

Existing inequalities exacerbated by the pandemic

The current pandemic has hit the poorest in our society the hardest: in exposure to the virus; in hospital admissions; in number of deaths; in job security; in food insecurity. The most vulnerable families are the most digitally excluded. They have the fewest resources for home schooling, the worst living conditions for lockdown, the greatest reliance on public amenities and facilities.

When it comes to COVID-19 I think we can see two things clearly:

The first is that one of the main drivers of poverty in the UK is structural inequality.

That second is that COVID-19 has highlighted and exacerbated existing inequalities.

Structural inequality

I know that Professor Brid Featherstone will talk much more about this when she describes the findings of the Child Welfare Inequalities Project.

What I want to highlight here is that the Child Protection System is itself deeply unequal in a structural sense.

What I mean is that, as my friend and colleague anti-poverty campaigner Moraene Roberts, points out, a defining feature of living in poverty in UK today is that social work referrals are part and parcel of people’s lives. However, this is not always viewed as something positive or beneficial. Social work interventions, particularly those centred on child protection are often viewed as hostile or inappropriately delivered by those on the receiving end.

When we consider the potential of such interventions to end in adversarial child protection proceedings and forced separations of families, the structural inequalities are stark.

The poorer you are the more this Kafkaesque experience is likely to happen to you.

‘Poverty-blind’ referrals

Why is this? Why is this so much more likely to happen to you when you are poor in Britain?

The obvious answer is that if you are in poverty, with so few resources and facing so many disadvantages, parenting becomes even more challenging than normal. But this doesn’t explain the whole story.

Child protection referrals and investigations are notoriously “poverty” blind. As Professor Kate Morris has said,

poverty is the ‘wallpaper of practice, too big to tackle, too familiar to notice’.

There are probably several reasons for this.

The first is that the structural causes of poverty are overwhelming and professionals find it easier to ignore it and focus on changing individual behaviour without contextualising it.

The second is that many professionals are wary of stigmatising families with the label of poverty.

I would add a third, which is that there is a lack of adequate training on poverty and how to understand it. Here, more training co-produced and delivered by parents with lived experience of the issues is greatly needed.

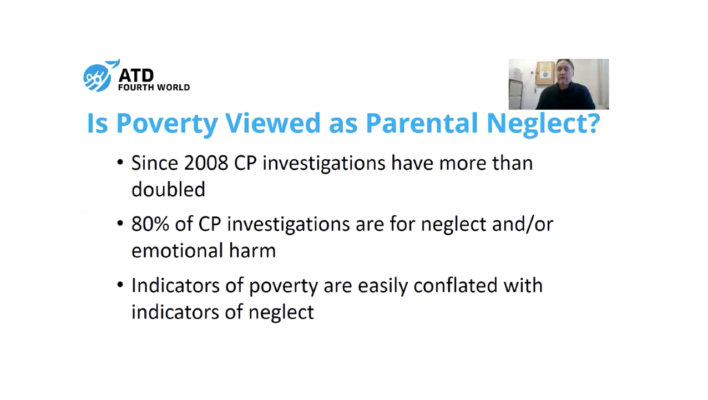

Conflation of poverty and parental neglect

I believe there is a fourth reason. In my work accompanying families through the Child Protection System, while supporting and advocating for them, I see time and time again poverty and parental neglect being confused and conflated.

Neglect and associated emotional harm are by far the biggest categories of abuse, as shown in these statistics:

- Children from the poorest 10 per cent of neighbourhoods are ten times more likely to be in foster or residential care than children from the least poor ten per cent of neighbourhoods.*

- Local area income inequality exacerbates rates of children taken into care and the social gradient in child welfare interventions.

- Around 75 per cent of the variation in rates of children in out-of-home care in England and Wales can be explained by underlying income deprivation and income inequality.**

The vast majority of these cases are not about intentional neglect. They are about the ability of parents to respond to the physical and emotional needs of their children. However, when you begin to look at the indicators of neglect commonly provided in child protection training it is immediately obvious, if you have any understanding of the impact of persistent poverty on family life, that indicators of neglect overlap extensively with indicators of poverty.

I would argue that, given the failure to recognise that parental capacities are severely compromised by persistent poverty, casting parents as unintentional abusers is extremely unfair.

A more accurate assessment would be that a very vulnerable family is suffering neglect. They are being neglected by society.

I would also argue that this is especially so, if we factor in the lack of access to early help due to a lack of services. If society’s response is to wait until crisis hits before intervening it becomes even more unfair.

Can shifting perceptions increase empathy?

When considering COVID-19 I think it is interesting to consider if perceptions of poverty have shifted. There seems to be more awareness and empathy for what it means to be struggling and vulnerable.

I think of several families I know who have felt trapped in their homes during the pandemic. One family lives in a high-rise block and during the lockdowns were terrified of leaving their flat with their children even for daily exercise due to the series of narrow corridors, lifts and key pads involved. Would they be judged as negligent in the current crisis? I don’t think they would.

I hope that any softening of attitudes can translate into more empathic policy and a new understanding of social protection once the pandemic is over.

Thank you very much

*McNicoll, A., “Children in poorest areas more likely to enter care”, Community Care, 28 February 2017.

**Morris, K., Mason, W., Bywaters, P., Featherstone, B., Daniel, B., Brady, G., Bunting, L., Hooper, J., Mirza, N., Scourfield, J. and Webb, C. (2018) ‘Social work, poverty, and child welfare interventions’, Child & Family Social Work, 23(3), pp.364-372.