‘You hear a child like me and you don’t hear me at all’

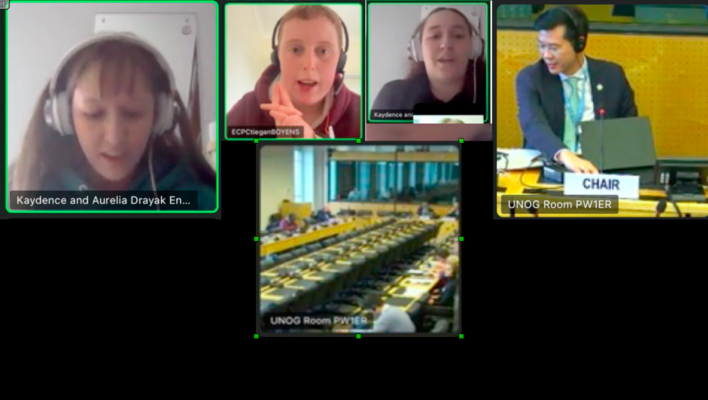

Above, Aurelia Drayak, Tiegan Boyens and Kaydence Drayak address the United Nations via Zoom.

Following a written contribution in December, on the 8th of March, Youth Voices (a project run by ATD Fourth World on behalf of the End Child Poverty Coalition) was invited to address the pre-sessional working group of United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights about its review of the UK Government’s compliance with the covenant governing these rights. Via Zoom, Aurelia Drayak, Tiegan Boyens, and Kaydence Drayak took the floor. Their remarks are below.

Aurelia: the nuanced knock-on effects

Thank you for inviting me to speak today, my name is Aurelia Drayak and I am a peer researcher from Youth Voices. Our submission to ICESCR was made by the End Child Poverty Coalition and Youth Voices. Something special that I want to emphasise about our submission is that we conducted lived-experience peer research, by young people about young people.

Peer research is valuable because we are better able to understand, communicate with, and accommodate the young people we’re working with because of our shared experiences and life perspectives. Our lived experience is an invaluable part of our research process and design because we’re able to understand the feelings and experiences of our peers, as well as allowing us to better make them comfortable and appreciate the fears and trauma they’ve been through in ways academics will find challenging because we have lived it. We know more than just what it feels like, we know what it sounds like, smells like, and what the nuanced and almost intangible knock-on effects are.

A care-experienced young person said:

“Help shouldn’t hurt this much.

[…] I want my home to be mine again

Together, our family has a good life

We don’t need inference and judgement

We could do with more money

But we can make do and get by without you

We don’t get a choice.”

Lived-experience young people are not always comfortable with professionals and other adults especially if they fear judgement. We’re able to make our peers more comfortable and show understanding and compassion in a way that professionals are incapable.

Thank you.

Tiegan: life-long impacts

Hello. I am Tiegan, a 21-year-old adoptee who spent two years in foster care before being adopted at four. There were many reasons I wanted to join and be part of this project, first due to the work I had done with the majority of this group where I found they were a very supportive and understanding group. We felt all very motivated to make a change and share our voices, as well as get other voices heard. So this seemed a perfect opportunity to do that, but more in depth.

The second was that I felt valued as an adoptee and still a social care-experienced person. Usually adoptees get forgotten out of that group, due to having left or been seen to have a better life. While in some ways true for some adoptees — and it’s good to focus on those who stay in social care, which is the case in our report — adoptees like me still have our experience of social care, our reasons for it and the life-long impacts, so it’s good to be welcomed into that.

Finally the major topic that this work was and is looking into is so key to many people and lives.

It is so common for poverty to be involved in some way when a child ends up in social care.

This was the case for me. We got moved to inappropriate housing care and my dad struggled with lack of funding. I feel this shouldn’t be the case. The right to family and safety are social care aims that so often aren’t reached not always due to their fault. These are tricky things to grasp, but at same time they are basics. I know from my own family stories, mainly with my sisters, how these are not achived on the daily. It’s heartbreaking to witness being unable to do anything.

‘It has opened my eyes’

As a peer researcher in this project, I wanted to engage fully with my role so I took all the training, which in its own way was very insightful. The disscuisons we have already had, and our engangment with others, have already given so many deep and thoughtful accounts of eexperience. I feel that even for me, it has opened my eyes to what things really can be like.

I think something so key about this project is that it has been driven by lived experience — and also driven by young people, which is even rarer. There is a lot of movement currently in many areas for lived experience to be part of and leading research and projects. This is slow though, so any project that has this is quite new. I feel this brings many benefits to the project, including that we have an understanding of the topics we are working on.

As much as we recognise we are only a couple, out of many experiences, we still have an understanding from our experiences. That helped us to work out what we feel would be valuable to ask and gain in this project and how. But at same time, we want other voices and are making sure they are key in anything we do. We hope you can see that in our report. There is also a real drive to make that change so we are committed. This brings us to add in other resources, like poems.

‘I can’t trust you’

Finally I want to share with you a poem we received that I feel speaks to me due my sister’s experiences of social care and the lasting impacts it had, as she was left to grew up in a unsafe environment.

“I can’t trust you”, by C, 14

[…] I’ve lost the ability to trust

I want to run away from you

But where can I hide from social workers?

Who do you think you are?

Running around leaving scars

Snatching away children

And tearing families apart

But you’re gonna get away with it

Because it is all in the name of ‘help’

So, I don’t trust you

Who do you think you are

I see you everywhere

You look like everyone else

So, you could be anywhere or anyone

I won’t trust anybody

I want to run away from you

But where can I run from social workers?

Kaydence: ‘The system can take away our sense of identity’

Thank you, Tiegan. My name is Kaydence Drayak. I am another peer researcher from the End Child Poverty Coalition and Youth Voices.

When we conducted our research, we ran focus groups with people who had lived experience of poverty and the care system. The focus groups consisted of both young people and adults with previous or current experience. Our discussions were semi-structured in order to be consistent but also allow flexibility. We shaped every focus group to the needs of those in the group and allowed everyone to explore the thoughts and views they felt were most important along with providing a more comfortable environment to talk about their experiences.

Speaking to those with lived experience, it is clear that identity is a big issue. When you are taken from your home, or have family members taken from your family. How do you know who you are? I myself am a big sister; that is what I consider one of the most important defining features of who I am. But who would I be without my siblings? My entire self is lost, and this is only one example of how the care system can take away our sense of identity.

This is an issue that professionals and academics are unlikely to identify. Unless you have had your identity stolen by those “helping” you, how would you predict this devastating consequence? This is why it is so important that we are able to have opportunities like this to be heard but also to lead projects such as ours.

‘You don’t hear me at all’

As a care experienced 9-year-old put it in their poem about the care system:

“You hear a child like me and you don’t hear me at all.

You visit a child like me and you don’t even see me, like I am not even real.

You think you know me but you don’t know me at all.

You make big decisions in my life when I don’t even want them.”

We can often be ignored but when we start leading we can make sure we are heard and our peers are heard. So you can stop making big decisions about our life without us.

Thank you for having us here to speak.