Reimagining Universal Credit

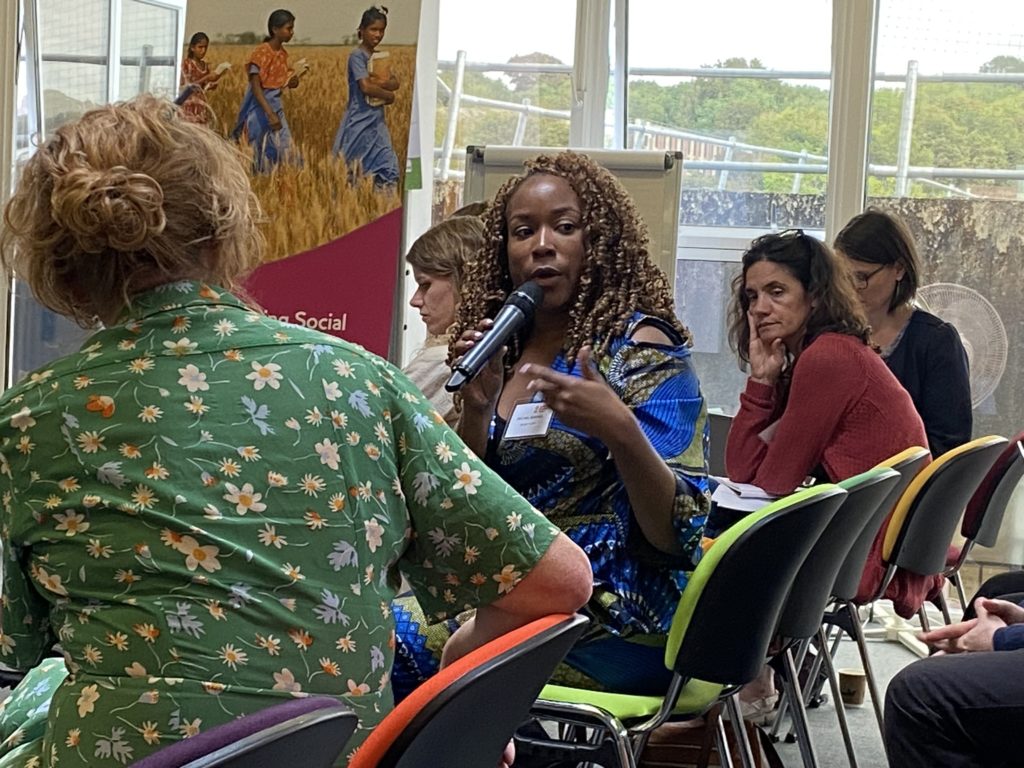

Above, Patricia Bailey speaks about her lived experience of Universal Credit.

ATD Fourth World participated in an international conference on welfare and social protection at the Institute for Development Studies (IDS) in Brighton, UK from 12-14 September 2023, called ‘Reimagining social protection in a time of global uncertainty’. The conference brought together researchers, academics, and representatives from UN agencies and civil society to discuss the state of welfare and social protection policies, mostly in lower and middle-income countries, but also in the UK.

Conference organiser Dr Keetie Roelen explains: “In many countries, such as South Africa, social protection has been expanding. In the UK, benefits have become a lot less generous in recent decades. In both contexts, people with lived experience are very rarely consulted on new policies or any changes to existing schemes. They are also often left out of conversations that take place in academic or policy-oriented conferences. In this conference, however, there was a panel dedicated to lived experience so that conference participants could hear and learn from those with first-hand experience of gaining access to social protections and having to negotiate their rules for eligibility and compliance along the way.”

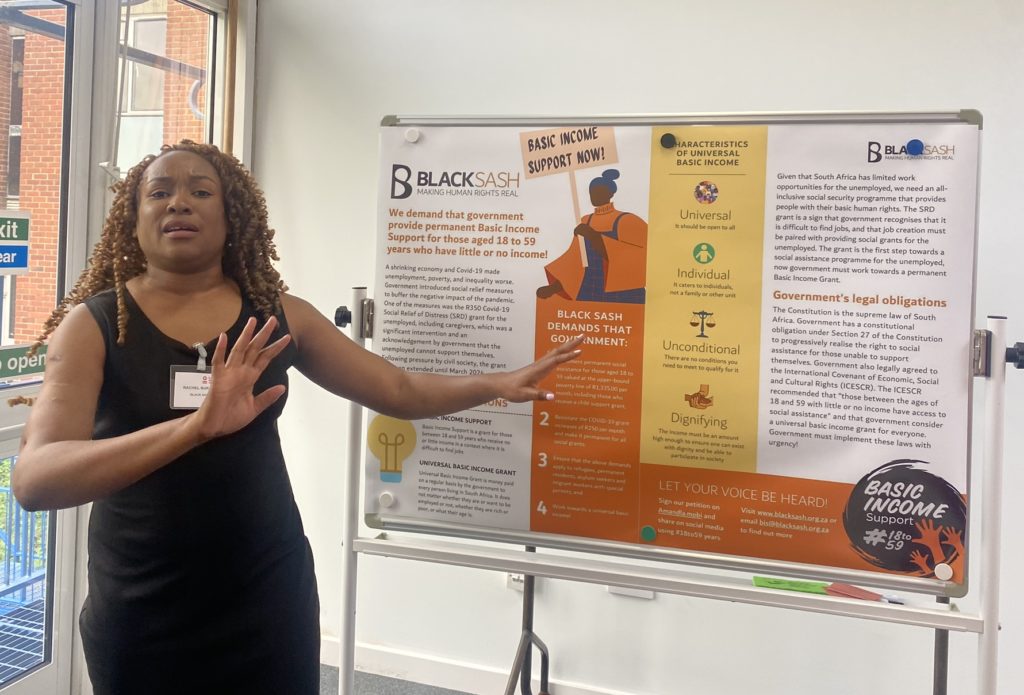

ATD members Patricia Bailey and Fran Bennett provided insights into the UK’s Universal Credit and the many problems with the policy. They were joined on a panel by Jo-Ann Johannes and Hoodah Abrahams from South Africa, who shared their experiences regarding the Social Relief of Distress Grant, a new benefit scheme in South Africa.

Keetie adds: “The panel was highly appreciated by the conference audience. During the conference closing comments, many participants reflected on how much they learned from the panellists, and on the importance of sessions focused on lived experience being part of academic and policy conferences.”

The full remarks prepared by Patricia and Fran are below.

Learning from Lived Experience

My name is Patricia Bailey. I’m an activist with lived experience of poverty. I’ve been part of ATD Fourth World for more than 20 years now. ATD stands for All Together in Dignity. A group of us senior activists with lived experience of poverty meet regularly as part of ATD’s inclusive governance to think about important decisions that we need to agree on together. And if you ask me, our governments would make better decisions about social protection if they got in the habit of thinking together with people who depend on protection to keep from falling through the cracks.

I’ve been working my whole life, since I was caring for my mum while we both worked in the same factory. But when you have kids and their father isn’t giving any child support, you need social protection benefits to help make ends meet.

Here in the UK, since 2013, they’ve been putting all the different benefits into just one, called Universal Credit. When they started, they kept saying it would make sure that “work always pays” by making sure we didn’t lose benefits by working extra hours. But as someone who has always worked, including all the way through the pandemic when I was working in train stations to help travellers, I can tell you that Universal Credit is a bloody nightmare!

First of all, you can’t even apply for it without having an email address and access to the internet. At the job centres, there are some computers you can use to apply—but if you’ve never used a computer before, you’re out of luck because no one has time to show you. So you had better find a way to figure it out quickly before it’s someone else’s turn to use the computer.

“It feels like a punishment”

Also, you can’t start getting Universal Credit without going into debt. This is because after you apply for it, it takes them 5 weeks to start paying you. They know that you need the money right away, and so they can give you a full month’s payment right away—but only as a loan. So they will be deducting it from your future benefits for a long time to come. I don’t understand why they need you to repay it when they’ve already calculated that you need it, and they have the money to loan you. Having to go into debt for it feels like a punishment.

The next problem is that when your agency needs you to cover extra shifts, your Universal Credit will go down—but not until the following month, when you might not get assigned many shifts at work. So you have to try to save money from the extra shifts or you’ll be completely broke the next month.

Another problem is that every time you get a Universal Credit statement, the numbers are different, depending on the shifts you (or your partner) have worked. And the statements are very confusing. That’s not just my opinion. With ATD, we go to teach social work students. We’ve given them an anonymous Universal Credit statement and asked them to work out how much the person has to pay in rent for their social housing that month. Not one of them can work it out because it’s very complicated. Why does the government send us such a complicated statement? It makes people feel like we have no power over our own budget.

And the amount you get is just not enough. You really have to stretch it to get from one month to the next so if anything goes wrong, your budget is out the window.

“Jumping through impossible hoops”

I have a friend on Universal Credit who also works while her daughter is in nursery. A few months ago, she had an accident at work where she got caught between two gates which damaged her ribs and lungs. The doctor told her to stay at home for 3 weeks. She showed that doctor’s note to get temporary sick pay, and then she returned to the same job. But at the Job Centre where they pay her Universal Credit, they decided this meant she had lost her job security because her sick leave was for more than 14 days. So for three months after she returned to the same job, they required her to prove that she was looking for a new job.

And they kept giving her appointments at the Job Centre just at the times that she was supposed to be at work! If she hadn’t convinced them to reschedule those appointments every single week, they would have sanctioned her with big fines. When you’re doing your best to hold down a job and keep your family together, I think social protection should be supporting you, not making you jump through impossible hoops and always threatening you with new debt deductions.

I live in one of the areas where they started using Universal Credit towards the beginning. They called it a trial. But then a few years later they rolled it out to the whole country without making it any better.

Why didn’t they listen to people like me to learn how to improve it?

Presentation by Fran Bennett

I will discuss to what extent Universal Credit was informed by lived experience; what key policy issues are raised about it by those with lived experience of it, as well as how they are treated; and what the situation is now.

How much was Universal Credit informed by lived experience in its origins and motivation?

Universal Credit was proposed in 2010, with legislation passed in 2012, and phased implementation beginning in 2013 (and still continuing now, probably until at least 2028). Those who proposed it, and the coalition government in 2010, had a clear idea about the causes of poverty, which included worklessness and ‘welfare dependency’, and it proved difficult to divert them from this.

In addition, Universal Credit was designed not around the real lives of those people who would claim it but around what the government wanted them to become. Universal Credit was described as ‘transformational’.

In addition, it was hard for anyone to disagree with the broad aims of Universal Credit, which included the simplification of a complex means-tested system of benefits and tax credits and an intention to make work pay and make more work pay more. This broad agreement may have meant that the details of Universal Credit were not examined as closely as they otherwise might have been

How much was Universal Credit informed by lived experience when it was put into practice?

Arguably the way in which Universal Credit was intended to work was informed more by economists’ modelling of financial incentives than by participatory or even qualitative research about the realities of lives lived in poverty and on benefits.

The government did publish some qualitative research with claimants of the previous system of means-tested benefits and tax credits.

But in couples the researchers only talked to the main claimant, whereas often it would be their partner who was in charge of budgeting the household’s money; and when they found that only one in ten thought that monthly payment of an all-in-one payment would help with budgeting, the government did not change these aspects of Universal Credit.

(Previously benefits and tax credits were often paid every week or fortnight, or weekly or four-weekly by choice, and some were labelled in terms of what they were intended for.) What the government did try to do was to persuade the private sector to let people set up ‘jam jar accounts’ to help with budgeting; but these turned out to be too expensive for those on low incomes and were not pursued.

When Universal Credit was introduced, the huge difficulties caused by the wait for benefit resulting from monthly assessment and payment in arrears resulted in several changes. The government abolished the additional 7 waiting days they had imposed. And there was a greater availability of loans (‘advances’) to tide people over and easier repayment terms. But the government did not introduce fundamental reforms to the structure of Universal Credit.

Evidence from lived experience of Universal Credit

There is now a significant amount of evidence from lived experience, obtained in a participatory way, not just from ATD Fourth World but also from participatory research in Northern Ireland by a project called UC: Us, as well as the APLE Collective, Poverty2Solutions and others.

Issues raised in this evidence include, for example, the inadequacy of the amount paid in Universal Credit; problems with the largely digital system; the algorithm used for the calculation of the monthly means test, with its cashflow approach, which leads to volatility of income from month to month for those with earnings or other incomes in particular; childcare costs, which for most people have to be paid upfront before being reimbursed; and Universal Credit being paid into one account for couples in most cases.

In addition, and importantly, how Universal Credit claimants are treated has been key in the testimony from lived experience. This is in part about having virtually all your eggs in one basket, because Universal Credit replaces a mix of different benefits paid by different authorities; so the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) is the body you deal with for most of your income.

And how you are treated revolves in particular around conditionality, which has been ratcheted up and expanded – including people in work but claiming Universal Credit. This involves punitive sanctions reducing benefits for those said not to be fulfilling the conditions, for a maximum originally of up to three years, now six months.

The situation now

The DWP seems to have become more open and is talking with ‘stakeholders’ more regularly – though these are largely academics researching Universal Credit and practitioners, including voluntary groups and welfare rights advice organisations. It also recommends claimants and potential claimants to independent benefit calculators to see how much they would get on Universal Credit; and it is more likely to refer claimants to the website for local advice organisations. But it does not really draw on lived experience from claimants themselves in its regular exchanges.

However, the devolved administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are dealing with Universal Credit rather differently. It is not a devolved benefit, so the UK government is responsible for it. But the smaller nations can and do vary its administration, by (for example) making alternative payment arrangements, such as more frequent payment than monthly, easier to obtain; and Scotland in particular has given additional benefits where it is able to. In addition, Scotland has also set up a panel of social security claimants which is consulted by the Scottish government about benefit policies, including Universal Credit; and it has committed itself to a social security system based on dignity and respect.

Some people have had a better experience of Universal Credit and have found some advantages over the previous (‘legacy’) systems. But ironically, in view of the government’s overriding aims about moving people into work, this probably applies more often to people who are out of work.

In the discussion, both Patricia and Fran responded to various questions and points from the floor.

Fran and Patricia visiting Brighton with Diana Skelton.