The power and impact of participatory engagement with the United Nations

On 5 July 2021, a fourth webinar took place to conclude the series called “Building a human rights bridge out of poverty”. Co-organised by ATD Fourth World with Amnesty International, Just Fair and the University of Essex Human Rights Centre, this series began last January and has included talks about the impact of poverty on the right to family life, and about human rights education, and the rights of people seeking asylum. The goal of this series has been to consider how to contribute to the United Nations review of the UK’s compliance with ICESCR, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

In the July webinar, Janet Nelson, who was the deputy director of UNICEF’s Geneva regional office, had a conversation with ATD activists Patricia Bailey and Amanda Button about what it’s like to engage with the United Nations and about the impact that lived experience can have on policy makers. The recording of the event is below, followed by written excerpts from their conversation.

Above: Janet Nelson (top left), Patricia Bailey (top right), and Amanda Button engage in dialogue.

Janet: Both of you have spoken at the United Nations before, and also to policy makers here in the UK and to journalists. What is it like when you are speaking from your own lived experience to people who don’t understand very much about poverty?

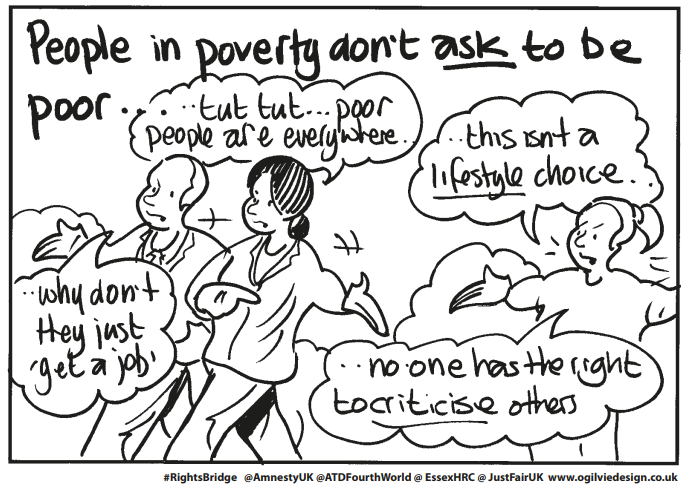

Amanda: Sometimes you meet people who blow things out of proportion and might have an image of poverty that isn’t true. They should take the time to get to know people properly. We once met a member of Parliament who was very nasty to us. She really didn’t want to waste her time talking to people in poverty. But no one has the right to criticise someone who isn’t as well off or as well educated as them. They may not have had the same struggles in life.

People in poverty don’t ask to be there, they do the best with what they’ve got. People in poverty are often treated without dignity and respect, which to me is disgraceful. They deserve the right to be treated equally with dignity and respect. After all, they are human beings just the same as anybody else.

Patricia: Once I was interviewed by someone who had no idea how her questions were coming across. She said she wanted to know what I thought, but she kept poking and poking. She dug in without really listening. She wanted me to talk at her pace instead of at my own. So I wasn’t comfortable talking to her at all.

When you’re talking from your own experience, pace matters and it’s also important to be able to protect your own boundaries. Last winter I supported a woman who decided to speak publicly about the impact of poverty on the right to family life. She was so angry about how the child protection system violates families’ rights that she wanted to speak out to make a difference — but then while she was speaking, she ended up talking about things that need to be confidential to protect her children. Next time, I told her she should prepare in advance to be sure about her own boundaries so that she doesn’t get in trouble. There can be serious consequences when things go wrong.

The importance of moral support and friendship

Janet: That point about boundaries is important. What other advice would you have to make sure that things go well?

Patricia: You need time to prepare carefully.

Going to speak somewhere new can feel very scary. You’ll feel better if you’re able to talk about it with someone else in advance to know what it will be like and to have the time to decide what you really want to say.

It’s also good to know that the person who helps you prepare will be there alongside you when you’re speaking publicly, just for moral support and friendship.

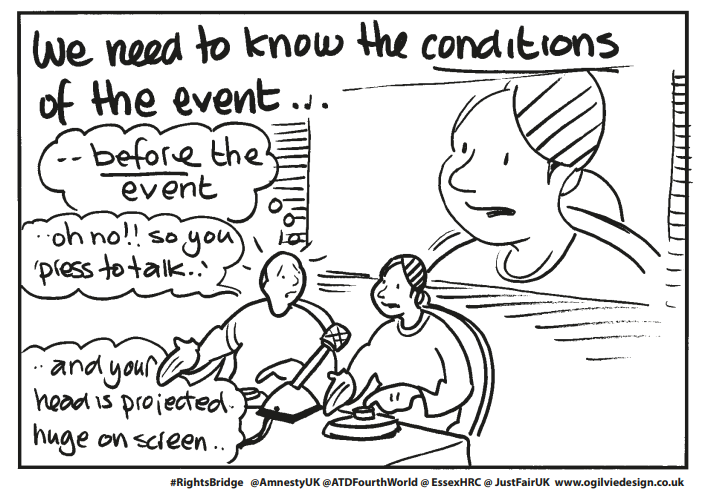

Amanda: You also need to know in advance exactly what the conditions of an event will be. Once I was asked to speak at the European Commission in Brussels. But no one told me that as soon as you press the microphone button, your head and shoulders suddenly come up on 200 monitor screens all around the conference room! I was gobsmacked.

You need to know how a meeting will be, who will be in the room, if someone is going to turn on a Dictaphone or a camera, and how much time you’ll have, so that you can prepare yourself.

You need to know how a meeting will be, who will be in the room, if someone is going to turn on a Dictaphone or a camera, and how much time you’ll have, so that you can prepare yourself.

The main thing is that if you do decide to participate in a public event, you make sure that you have enough time to prepare your main points and that you can be accompanied so that you feel confident and comfortable and not pushed into anything.

Giving voice to other people’s struggles

Janet: That preparation to respect your boundaries and to increase your confidence is very important. Have you also had positive experiences with speaking from lived experience?

Amanda: Definitely. In 2018, I went to Brussels to speak at the European Commission about the importance of involving people with lived experience of poverty in research. We got good feedback there. They recognised that it can sometimes be hard to speak up in this setting if you don’t have confidence. At the beginning, I would not say ‘boo to a goose’, the nerves would have kicked in. But now I’ve been coming to ATD Fourth World for over ten years so that I feel like I have grown in confidence over the years due to the peer support from other activists.

I saw others with more experience speak naturally from the heart. I learnt from them how to conduct myself in public, not to be ashamed by what I say, and the experiences I share.

I learnt to give voice to other people’s struggles and suffering, and also share from my own experience; but at the same time I’ve also learnt that you should only say the things that you are comfortable with, just like Patricia was saying.

Patricia: It’s true that having a peer support network before you speak out means we can help each other to say no when we’re not comfortable with the way a question is asked. We can think about what our own boundaries are. It can be nerve-wracking to meet new people from a different background, but now I realise that when we go some place new, the people we meet are sometimes nervous about meeting people with lived experience of poverty too.

Amanda: When we have the chance to meet policy makers, we do not just represent ourselves. We represent others that are in poverty who might not be ready to speak out; but if we can get the points across to the people who have the power to make a difference, it can be a win-win situation.

The impact of lived experience on UN policy makers

Patricia: Now it’s Janet’s turn to answer questions. When you see people in poverty speak at the United Nations, what happens when they leave the room? How do the people at the UN listen to what we have to say?

Janet: People are often quite surprised and impressed by what you have to say, because

your statements go against many of the stereotypes they have of people in poverty.

People who have never experienced poverty often don’t realize the many forms of discrimination that you face, and all the factors that keep you from being able to lift yourselves out of poverty. They also aren’t aware of how hard you fight to try to make a better life for your children, and the ways in which our institutions work against you and not with you. And so it’s important that they hear your voices.

I remember when we were lobbying the members of the UN Human Rights Council to develop and adopt the Guiding Principles on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights. There was some resistance, because so many people believe that poverty will be resolved by economic development.

It was on hearing the voices of people with a direct experience of poverty that they realized the many forms of maltreatment that lock people into poverty.

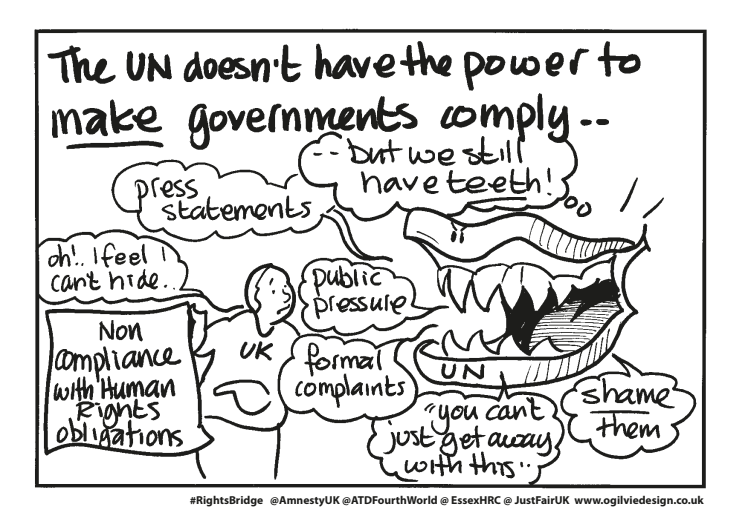

And so they ended up adopting the Guiding Principles that affirm that extreme poverty is both a cause and a consequence of human rights violations. The fact that international institutions are above national governments means they can influence national policies.

The impact of poverty on the right to family life

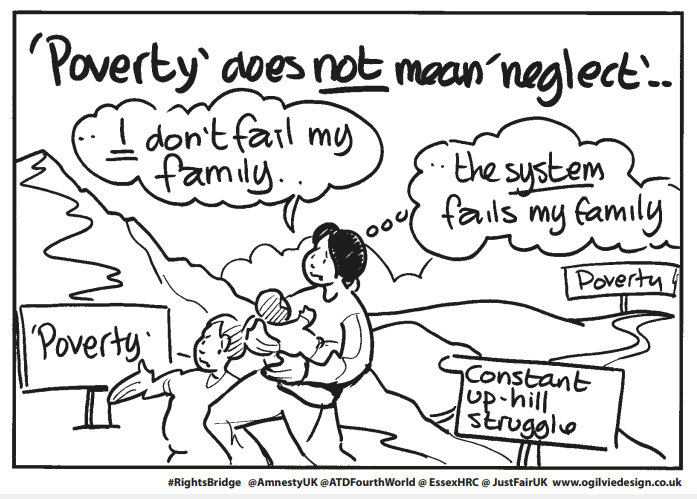

Amanda: One of the human rights issues that we want to move forward is about the impact of poverty on the right to family life. A lot of the social workers here will see a family in poverty but they’ll mix up indicators of poverty with indicators of neglect and end up taking the children away from the parents. How do you think we could use the ICESCR review to talk about this?

Janet: The fact that the system too often considers problems to be the result of parental failings, rather than failings by the system, is an explanation for the facts around the number of children placed in care or put up for forced adoption. This means that the State is not living up to the ICESCR obligation that says:

“The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize that:

-

“The widest possible protection and assistance should be accorded to the family, which is the natural and fundamental group unit of society, particularly for its establishment and while it is responsible for the care and education of dependent children.” (article 10)

-

“The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions.” (article 11)

The fact that the voices of families in poverty are not heard contributes to the fact that the right of families to non-discrimination is not upheld:

The fact that the voices of families in poverty are not heard contributes to the fact that the right of families to non-discrimination is not upheld:

“The States Parties to the present Covenant undertake to guarantee that the rights enunciated in the present Covenant will be exercised without discrimination of any kind as to race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.” (article 2)

Although the ICESCR’s concluding observations do not impose action on a country, whenever it calls a government to account, that is one more way of putting pressure on it to improve its policies. And so in this case, making a submission to the ICESCR review is one way to continue working on the issues that were raised by the 2018 visit to the UK of the UN’s Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights, and to be sure that they are not forgotten.