Poverty-Aware and Anti-Poverty Social Work

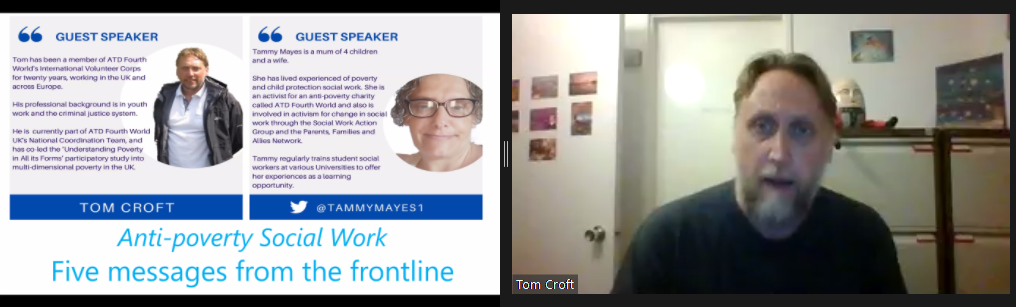

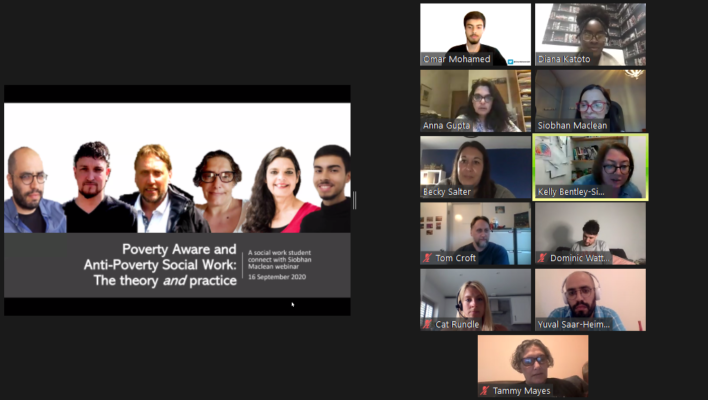

In September 2020, Siobhan Maclean (Honorary Secretary of the International Federation of Social Workers) hosted a social work “Student Connect” webinar entitled: “Poverty-Aware and Anti-Poverty Social Work: the Theory and Practice”. Thomas Croft and Tammy Mayes spoke on behalf of ATD Fourth World. Their remarks are below. The recording of the webinar can be seen here.

Remarks by Thomas Croft

Poverty is multi-dimensional

What do we mean when we talk about multi-dimensional poverty? It is a way of saying that poverty is a complex reality, that poverty is so much more than living on a low and inadequate income. At the human level, poverty affects every aspect of a person’s, a family’s, a community’s life.

From 2016 to 2019 ATD Fourth World, in partnership with professional researchers from the University of Oxford, carried out participatory research in the UK to better understand poverty in all its forms. This was a ground-breaking study because people with direct lived experience of poverty took part as co-researchers at the heart of a large research team. They worked alongside co-researchers with professional experience of poverty from fields such as social work, journalism and the NGO sector.

They took responsibility jointly for the design of the research, carrying out the fieldwork, analysing the data, writing up the results and deciding on the messaging. Tammy’s husband Thomas Mayes was one of the co-researchers on the project and I was part of the operational team taking instruction from him and his fellow co-researchers.

The study formed part of an international research project called the Hidden Dimensions of Poverty that pulled together the results in six different countries: the UK, France, the USA, Bangladesh, Tanzania and Bolivia. In each country, focus groups brought together adults from communities living in poverty, and professionals, academics and practitioners. Participants worked with their peers to share their experiences and then to identify together the different dimensions of poverty.

This was a deeply participatory approach which recognised that we need to build knowledge of poverty in partnership with people in poverty where they are equals in the process.

In and of itself, deeply participatory research promotes epistemic justice because it recognises people’s expertise and provides the conditions for people to name and conceptualise their experience together with other more recognised experts.

What did we learn?

We learnt that the dimensions of poverty are remarkably consistent across different countries. The core experience of poverty in each country was one of disempowerment, of suffering in mind, body and spirit, and of constant struggle and resistance.

We identified well-known dimensions of economic, social and material privation – but the narrative was deeply human. We kept hearing stories and examples of people continuously being denied opportunities and choices that are taken for granted by the rest of society.

Of having little control over where you live, what you can afford to do. Having your horizons restricted. Your freedom curtailed. There was a strong feeling that poverty’s attack on people’s autonomy and liberty was dehumanising. That poverty was dehumanising.

Next we found a set of deeply relational dimensions which described how social exclusion is an active process that people experience as various forms of social and institutional maltreatment. In the UK, people spoke about: being bullied by the benefits system; facing hostile social service interventions; being ridiculed and humiliated in the media; often feeling rejected, blamed and judged by their fellow citizens; being patronised or treated with disdain by many of the professionals that were supposed to help them. People also told us how their efforts and strengths as individuals, families and communities were often ignored or devalued; how their contribution to society went unrecognised; how the roles they played were overlooked. How their knowledge was dismissed or denied.

Yes, the causal drivers of poverty are deeply structural, but they are also deeply relational on the level of human interaction and human relationships. Seeking to understand this and reflect on this should be a constant part of a social worker’s reflective practice. You may not be able to directly challenge policy but you can help to overcome poverty through treating people in its grip with respect and dignity.

Put the “social” back into social work.

We know that poverty has deeply social, deeply relational dimensions. Poverty is intimately linked to social exclusion, to social isolation. But people in poverty also have families and neighbours and belong to communities. They have their own networks of mutual support.

Part of my job at ATD is to support families going through crisis, particularly when those crises lead to social work interventions. I am often asked by parents to accompany them to case conferences, sit alongside them at the family court, or go with them when they are summoned to a meeting at their children’s school.

A large part of what I do in this capacity is to help people to understand the reports and papers that are written about them and their children and to help them keep track of and understand the process they are in.

For many, a child-protection investigation can be a Kafkaesque experience. I also spend a lot of time helping parents to work through their emotions and think through what they want to say or ask at a meeting. Everything is parent-led.

Parents ask me to support them in this way because we usually have a pre-existing relationship in another context at ATD. We take part together in other projects with other people. We are part of the ATD Fourth World Community. For example, we offer respite breaks to families at our residential centre, Frimhurst Family House. These are called “holidays from poverty” where people get away from it all, get away from the stress and pressure, where they can relax, recuperate and have fun in a safe, secure and non-judgmental environment. Where they can create happy memories in a beautiful setting.

Frimhurst is a large country manor house set in several acres of wooded park land that was given to ATD by a remarkable women called Grace Goodman. She was an independent social worker with a deep vision. She believed that families in poverty were often traumatised by their lived experience of poverty and needed spaces and places where they could rebuild their strength and enjoy the freedom to turn hope into action at their own pace, to, as one participant in our research project said… “smell the flowers again”. When we run these breaks, my wife and my kids all take part together as a family too. We try to break down barriers. We are all on holiday together.

Why am I telling you this. For two reasons.

First, because I think something is going very wrong in the way social work is often carried out. The focus is too much on the individual and too much on their difficulties and problems, and not enough on the individual as a person with strengths and capacities who plays many important roles within their family and within their community.

Secondly, in my experience poverty is overcome when people have the opportunity to enrich their human relationships, when they can build connections with others, with their peers – with others who are going through what they are going through – but also with others from other backgrounds. When they can invest in their existing relationships in new settings and contexts. When they can be part of something with others.

Recognising this relational dimension of anti-poverty practice is something that I believe should inform any new paradigm of social work.

More than this, social work needs the knowledge and insight of the people who have to rely on it in order to renew itself. This is an important part of what ATD is trying to achieve alongside parent activists like Tammy beside me.

Remarks by Tammy Mayes

Poverty is not neglect

Hi, my name is Tammy. I am a mum to four children. Two boys, aged 21 and 20. And two girls, 16 and 14. I am a wife as well.

The first thing I want to say is that poverty is not neglect.

Not long after we had our boys, we were made homeless due to no fault of our own. Social services housed us eventually but would only house me and my boys. Hubby was not allowed to come with us. They sent me to a B&B, away from all my family and hubby. I had to leave the B&B at 8am and was not allowed back until 7pm. It was a nightmare on my own with two babies. That was poverty, not neglect.

Parents can feel that professionals are prejudiced against people in poverty. My family had to use a food bank after our washing machine broke just after we had come back from holiday. We had been paying for the holiday for a full year beforehand, and we had no money while we were on it. At the same time, we also had to pay the council tax. That was poverty, not neglect.

But none of this was mentioned or explained. It was said that we used a food bank because we didn’t know how to budget and that using a food bank was a sign that we were neglecting our children! I have told this story to social workers that want change and they are shocked at our experience. But there are loads of stories like mine out there.

What professionals (and it is all professionals; schools, doctors, mental health, social workers) don’t seem to get is that most people in poverty will go out of their way to help others. They will go without themselves and live on nothing but one meal or a bowl of cereal just so their children don’t go without. They might not be able to go out the same day the school shoes break or the trousers get too small but they do as soon as they can. People in poverty budget everything but there is no money left over for emergencies. Unfortunately like all walks of life you get the bad people that do neglect their children but not all parents are like that.

No one chooses poverty or disabilities. And they don’t go out and say, “Oh, I know, I will have a child with disabilities!” Yet we get blamed for it. We feel we get discriminated against all the time and it is wrong. Because poverty is not neglect.

The next thing to say is that poverty-aware practice restores dignity.

I have been involved with ATD Fourth World as a family member for 18 years and 10 years as an activist. I have done a lot with ATD. One thing I did was The Roles We Play project. Which we made into a book and exhibition about how people who live in poverty are not all layabouts. We do stuff in our communities and we have goals. I gave a copy of the book to a social worker that was in our life at the time and they told me they found it really great and even took it back to their office for everyone to read.

This is proof that there can be relationships between parents and social workers. We are people just like you. We have views and values, too, just like you. We also want to protect our children just like you.

Treat us as human beings and not a number and understand that family life cannot be taught through a text book. Life is unfair and when people realise this the world will be a better place. Parents don’t choose to live in poverty or to have children with disabilities/illnesses, we just have to deal with it as best we can. Parenting doesn’t come in the form of handbook. Every family is different and even if they have the same issues, people deal with stuff differently.

This is why positive relationships are so important. Parents will judge social workers and social workers will judge parents but we both need to be open to the other side. One key thing in changing the system is being open to the dynamics of the family and not relying only on what is written in a report.

One social worker was great. When she came into our life she said that the reports were before her time and that she wanted to get to know us as a family. She took a look at the reports but did not read them fully. We all worked together and we spoke openly with her but then we always do. We have always worked with social services even when we have disagreed with them. You might be wondering why? Well, the reason is simple. Our children come first.

Peer support and parent-led advocacy are vital to change the system

Finally, I want to tell you about how important parent-led advocacy and peer support are.

Shaeda is a family support worker and advocate from ATD who helps families with stuff they have going on in their lives but doesn’t tell us what to do.

She supported us when our daughters got put on a child protection plan because some professionals accused us of neglect and helped us to keep a level head. When you’re going through the process you go through loads of different emotions: upset, anger, feeling like a failure despite feeling you haven’t done anything wrong. And you worry about what’s going to happen and whether they will remove the children.

Shaeda was on our side and we knew that. She was someone we could talk to about what was going on, so we could get our heads around the legal jargon and properly understand what was happening.

I was often scared not to have understood things. It’s so hard to listen to what people are saying in the local authority meetings. You can get emotional. You try hard not to show that you are angry and this is why you can miss what is being said. Shaeda took notes in all our meetings and took the extra time to go through all the paperwork with us. She was someone that also understands our family.

Being a member of ATD Fourth World also allows you to meet other parents who have been going through similar things. It gives you a peer support network. It’s like a sounding board. You always have someone to talk to when you are having a bad day and vice versa. Someone who has been through it themselves. We feel listened to, feel supported and can give each other advice.

Throughout the proceedings I had friends from ATD I could talk to when it was too much. A lot of my own friends outside ATD have not been through it and did not understand it.

ATD also brings parents like us together so we can think together and take action. Go to conferences and also help train social workers.

I have been part of the Social Worker Training Programme for nearly ten years now. It was strange at first because we were talking about our own experiences and how we felt social workers are and what should be different. As it’s gone on the project has changed and we made friends with social workers and we work together. And we learn from each other.

Also we get to look at it from the other side because getting involved in training social workers helps us to understand things from a social worker’s point of view. We can look at it from their angle and see they are under pressure from their managers.

Being involved in the Social Worker Training Programme and the study groups has helped us to understand better our rights and to also understand what the system is like.

It’s very important to me because it is about reassurance and another way of not feeling alone. We are not alone in fighting the system. We have professionals alongside us as well.

Thank you.