A history of Frimhurst Family House

In 1957, Frimhurst opened as a residential centre for those then considered to be “problem families”. In the economic boom that followed World War II, social workers considered that anyone who did not manage to escape poverty must “have problems”. Another factor behind the creation of these residential centres was the housing shortage caused by wartime destruction. This led to unauthorised squatting by homeless families, often in former military camps.

When the authorities decided to clear out the camps, they needed residential centres. Seven such centres opened throughout England based on a social work approach of lowering caseloads and encouraging intensive interaction. These places were called “recuperative centres to assist and rehabilitate ‘problem families’”. Most such homes were managed by “wardens” or “matrons” whose goal was to instruct mothers in domestic tasks such as cooking, cleaning, sewing, and a strict approach to child care. Mothers and children were sent to these centres for several weeks without their husbands, who were not considered to have a role in the household beyond that of earning money. In these centres, each warden’s authority was absolute; thus, whenever a new warden replaced an outgoing one, all house rules might also change.

A participative ethos

Frimhurst, however, functioned quite differently from all the other centres. It was started by Grace Goodman and Margaret Gainsford, both formerly specialised family social workers. Their approach was based on a more participative ethos. The whole family was expected to arrive together, rather than mothers and children alone. Admission was signifcantly longer, for months rather than weeks. Families were encouraged to fnd value in each member of their family. At a weekly meeting of all residents and staff, parents could complain about one another but also about the residential staff and about the way the centre was run: something unthinkable in any other centre. All of this differentiated Frimhurst from other centres. Frimhurst maintained a ferce independence, guided by valuing families

In 1961, Joseph Wresinski, founder of ATD Fourth World, traveled to the United Kingdom, visited most of its residential recuperative centres, and met the key people who had designed them. The personality of Mrs. Goodman along with the exceptional atmosphere of Frimhurst led to his enduring friendship with her. In 1967, he asked Mary Rabagliati to join Grace Goodman at Frimhurst.

‘Unacceptable’

Mary recalled: “Joseph Wresinski spoke to me and the other volunteers, saying, “Now that the families living in the camp of Noisy-le-Grand are going to be rehoused, we must go and build this movement somewhere else.” I was one of the first to disagree because I was worried about the families in the camp. I thought that what we were trying to achieve with them would fall apart. Fortunately, however, Wresinski insisted. In fact, as long as we remained in the chaos of the camp, we were holding ourselves back and limiting our vision. By leaving that chaos, we became freer to work on behalf of people in poverty in other countries.

“Shortly thereafter, Wresinski asked me to return to England to join a project called Frimhurst. When hei visited Frimhurst, he discovered that, like ATD Fourth World,

Frimhurst was also making a priority of families who were considered by others to be “hopeless” or “useless”. These are families who actually feel they have been discarded by society. They have a feeling of failure. They live in intolerable conditions that are impossible to believe until you witness them, and they have a sense of isolation and loneliness that can be greater than any other diffculty. It is unacceptable that anyone be treated this way. Their situation should push all of society to rethink who we are as people.

Extraordinary freedom

“Joseph Wresinski and Grace Goodman agreed that this excluded population actually had a great deal of potential that others did not see. He sent two of us to create a lasting connection between Frimhurst and ATD Fourth World. Above all, we wanted to learn from Mrs. Goodman. At that point, ATD had quite a lot of experience, but Wresinski always felt that there was more to learn from others. He knew there are people all over the world who stand alongside very poor families, all in different ways, and he wanted us to learn from them. Our goal was not to become the ones who know everything, but constantly to renew our motivation and our way of working against poverty. I found that approach captivating.

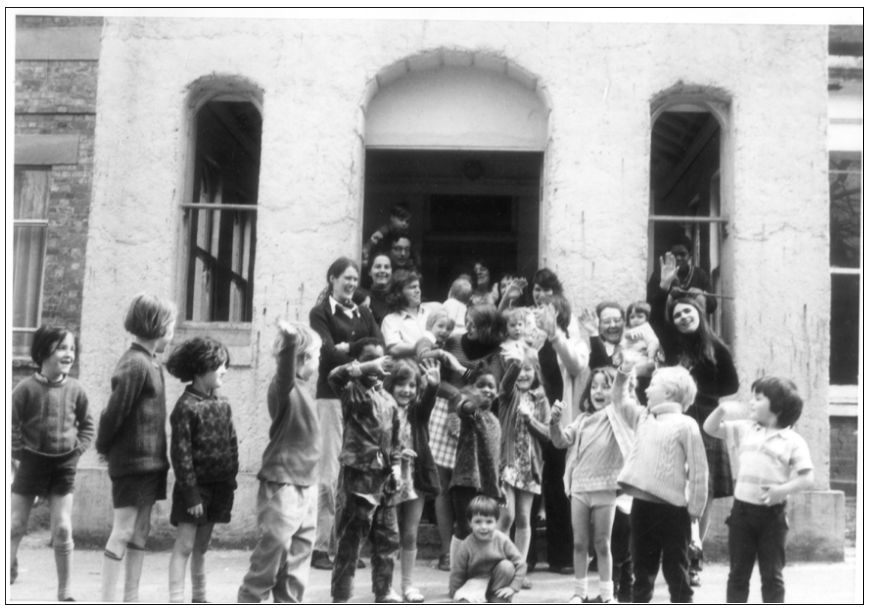

Above: At Frimhurst in 1972, Mary Rabagliati is the adult at left.

“Mrs. Goodman was a woman who felt extraordinary freedom to speak her own mind and make her own choices. She wanted to offer that same freedom to families in poverty. The families there had spent generations being dependent on the good will of others. She wanted them to feel free enough to make their own choices, and then to take responsibility for making their choices work. Mrs. Goodman had a great capacity for meeting others and going straight to the heart of the matter. She was brilliant at developing relationships. But she had not structured anything, and she never explained anything. You had to follow her around with a pencil and paper. You had to observe her to try to understand.

“Nobody had ever questioned her before. When we began asking questions, this enabled her to begin putting her approach into words. She said she had no pedagogy; but what she did was to accept people as they were, without judging them. She did explain her way of respecting families and told us her hopes for them. She was curious about people, and that gave her a way of understanding people’s suffering. Everyone trusted her, both people in poverty and people from any background. She took time to get to know everyone who crossed her path. She spoke of the people we welcomed at Frimhurst as ‘families who have lost heart and feel they have been got at by society’. The approach that we used at Frimhurst was to have faith in these families to start with; then they began to have faith in themselves.”

To learn more about the history of Frimhurst Family House, please see “They Deserve the Stars“, an animated video about Mary Rabagliati’s years there, and “The Creation and Endurance of Frimhurst Family House“, based on doctoral research by Dr. Michael Lambert of Lancaster University.