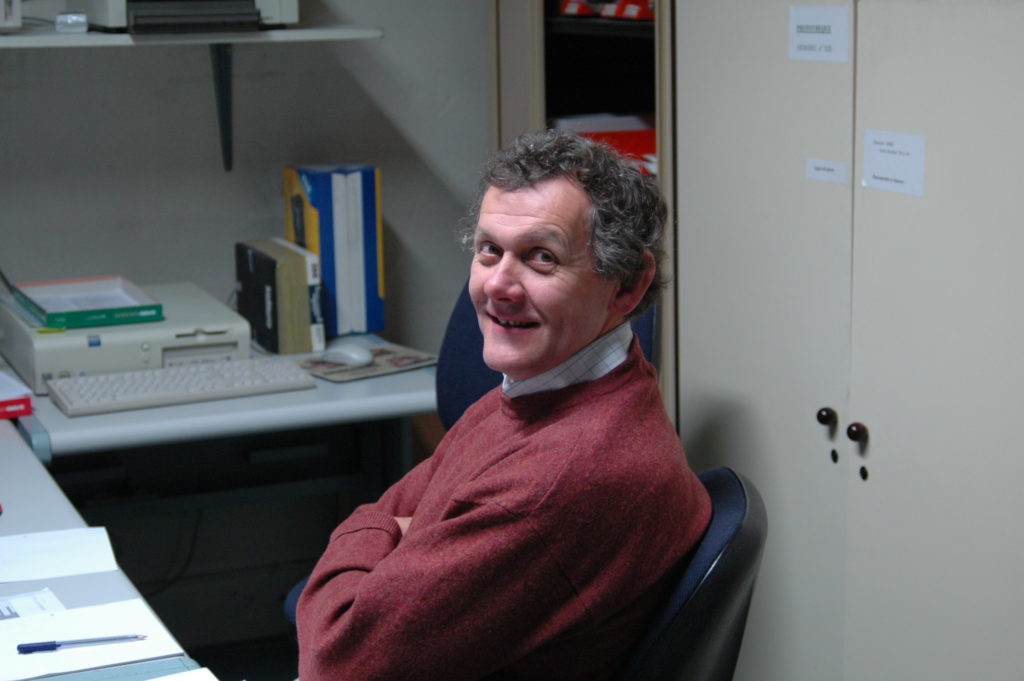

Remembering Jean-Luc Penet: ‘Human rights are intrinsic to our work’

It is with great sadness that we have learnt of the passing of Jean-Luc Penet, who died after a short illness in Paris on 20th June 2023. In 1991, Jean-Luc, his wife Marie-Hélène, and their five children came from France to spend ten years with ATD Fourth World UK. Jean-Luc’s impact on the development of ATD Fourth World UK and on the anti-poverty movement here during that decade was critically important.

With his determination and energetic commitment to social justice, he inspired a generation of activists and campaigners to challenge the terms of the debate on poverty and the conception of anti-poverty action. He and Marie-Hélène can also be credited with introducing an enthusiastic generation of young British people to ATD Fourth World’s International Volunteer Corps, which he first joined in 1977.

After spending almost three decades with the Volunteer Corps, he chose to forge a new path by offering therapeutic support to people suffering trauma. He leaves behind a significant legacy.

Below, we are reprinting extracts from an interview of the Penets in 2001, first published in the Fourth World Journal on the occasion of their leaving the UK to take a new responsibility in France as part of ATD’s International Volunteer Corps.

Jean-Luc: When we first moved to London ten years ago, no one in our family could speak English. It was not at all easy! I was used to speaking to many people and running projects. Suddenly, I felt completely disempowered and useless. I worked as a cleaner and delivered pizzas for a while. During this time, I was able to feel closer to families who cannot speak for themselves and who remain silent because society has no real time for them.

Marie-Hélène: Yes, and we felt very close to immigrants. I especially felt for their children having to cope at school. It must be such a challenge for them. At the same time, we felt very lucky to be a family and to belong to ATD Fourth World. We were not completely on our own.

But we didn’t expect it to be so difficult coming to the UK. We thought we were going to a country very near France and probably quite similar. In fact, we discovered a very different culture. If we had been going to Thailand, we probably would have prepared ourselves in advance. We certainly did not expect that we would not be able to recognise the meat at the butchers or the makes of soap!

Was being a foreigner in the UK a weakness or a strength?

Jean-Luc: To start with, it was very strange and hard. I could not write properly in English on my own. I always had to count on other members of the team. I learned to be humble and to depend on others all the time.

But this weakness has become a strength over the years. For example, when a family in poverty would ask me to do something for them, I couldn’t. I had to tell them:

“I cannot speak for you. You are able to do it yourself! I can support you by being alongside you, but I don’t know the answer. Let’s go together.”

In this way, the most vulnerable families helped me to discover British society. I had the privilege to work with Moraene [Roberts], Tricia [McConalogue] and many others who really carry in their hearts the families who are hardest to reach. They have the ability to convey with great strength the message of those who experience the realities of poverty. I hope they will continue to inspire many others.

Because I didn’t understand how institutions work here in Britain, I was able to ask advice from people in many sectors of society. I am very grateful to all those people who really helped me to do my job properly, such as Fran Bennett, Bob Holman, and others.

Being a foreigner, I had to be open to following a lot of outside advice on how we should do things to become more known and efficient in the British context. But at the same time, I had to make sure that we were remaining faithful to the ethos of ATD Fourth World. Maintaining this balance between trusting others with decisions and yet making sure they respect our ethos has not always been easy, but it has defined my role here. I always saw my role to be that of a facilitator, allowing British people to take a stand, rather than as director or a main spokesperson.

What do you feel to be the main achievements of your time here?

Jean-Luc: The fact that we have published books in English is something to be proud of: Talk With Us, Not at Us; Participation Works; Education: Opportunities Lost; and Out of the Shadows.

Many parents use Talk With Us as a tool to tell social workers: “I am not just someone with difficulties in coping. This is the work I have been involved with.”

More and more, we see academics refer to our books in their research.

The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Poverty (APPGP) is another important success. I remember talking about this idea in 1993 with the director of a national charity. He said: “It’s a continental concept that will never work here”. And yet, in 1996, the first ever APPGP in British Parliament was set up, backed up by MPs from all parties and supported by the UK Coalition Against Poverty, of which we were a founding member. What’s unique about the group is that people in poverty have the opportunity to discuss issues directly with MPs and Ministers. It is unique in Europe.

An intense moment for us was the first APPGP. We were preparing very hard with people living in poverty, supporting them to get their views across.

I was petrified beforehand. I was thinking, “If it doesn’t work, I will get the blame”. But by the end, I felt I could carry on forever, it was going so well. I felt so proud listening to the families in the House of Commons, asking questions of the Minister.

[To learn about ATD’s current collaboration with the APPGP, please click here.]

There were many occasions on which I could feel the pride amongst the families we are involved with. We went to the House of Commons together to launch The Wresinski Approach in 1991 [see page 16 of ATD’s book catalogue], and then in 1996 and 2000 to launch Talk With Us, Not at Us, and Participation Works. There were different audiences and new lived-experience activists each time, but the same pride.

Which have been your proudest moments?

Jean-Luc: I would mention Sarah and Steven. For ten years, they have been living together, moving from one city to another, having lost all their children into the care system. But just after one Christmas, Sarah gave birth to Jason. Three years later, Jason remains with his parents, who are very proud of their son and of their achievements. They are so happy to have been able to stay on the South Coast in the same place for three and a half years.

A few weeks ago, I met with a woman who is very active in her council estate. She is very articulate and a good spokesperson for her community. She asked to meet with me and spoke about her personal circumstances, having lost some of her eldest children into the care system. She said, “I never mentioned this to anyone else”. I felt very privileged.

I am always amazed by the courage of many parents I have met, so many of whom have lost their children into care. It is wonderful to see so many of the people who are struggling in poverty to find inspiration in the work we do and who later say: “This is the organisation I feel I belong to”.

What has been most challenging?

Jean-Luc: Not everything has been a success — far from it! To fundraise, you have to work hard and often get nowhere. It is still difficult to express the ethos of ATD in a funding application, especially if you don’t have face-to-face contact with the people with the purse strings.

We have had a very poor record accessing the media. Progress has been made in professional magazines, but not in the national papers or television, apart from a few exceptions, such as parents being invited twice to speak on Newsnight.

A much more serious challenge is the fact that

many children are still taken away from their parents because of alleged “neglect”.

The Children Act 1989 was a real hope for many parents when it came into force. But from working in partnership with parents and supporting them, the focus has moved too much to child protection. There is a massive lack of human and financial resources. Too many professionals spend too much time filling in forms instead of doing face-to-face work.

I would like to pay tribute to Teresa, who was living on the street after her children were taken away from her. She died at the age of 43. Today, her children probably don’t know that their mum is dead. We gave information to social services, but they just filed it for the children to have access to if they want to find out when they are over the age of 18. They refused to tell the children, which is a total disgrace.

What openings are emerging for the future?

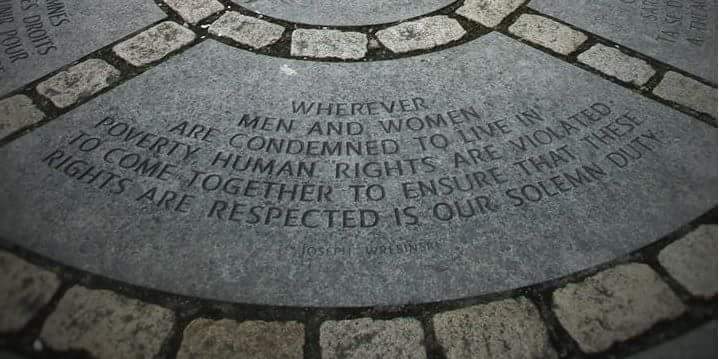

Jean-Luc: The issue of human rights is intrinsic to our work. I really hope that the Human Rights Act will bring back a culture of rights to uphold the rights of the most vulnerable citizens who are often abused by the system.

Some lecturers have begun to recognise that their teaching has to change, especially in the field of social work. Some academics too recognise that they can no longer do research on poverty in the same way. Both recognise the need to involve people in poverty themselves as trainers and actors, and to no longer consider them merely as the subjects of studies or teaching.

There is a quiet yet deep revolution of mentalities going on.

With Moraene, Prof. Jane Tunstill of Royal Holloway College, Jane Wiffin, senior researcher at Making Research Count, and others, we are looking at how to involve parents in the training of social workers and in researching family support.

[To learn how these initiatives developed since 2001, see here our project on anti-poverty practice training, and here what it was like for people in poverty to become co-researchers alongside academics in 2016-19.]

How have your children experienced their ten years in the UK?

Marie-Hélène: They are now aged from 15 to 24. They grew up discovering both worlds: by attending the French Lycée, and yet living in Camberwell and meeting families in poverty through ATD. It has been a real shock for some of their school friends to discover that they live near the Old Kent Road, the cheapest street on the Monopoly board!

Sharing the house with young British, Australian, Swedish and American residential volunteers has also been very inspiring for our children. We hope that the whole experience has enriched their understanding of human beings and better equipped them for life, whatever career or life choices they go on to make.

Jean-Luc and Marie-Hélène: To all of you who have helped, supported, inspired, challenged and motivated us, we want to say thank you very much.